How Maori Activists & Their Lawyers Reinvented New Zealand’s

Treaty of Waitangi

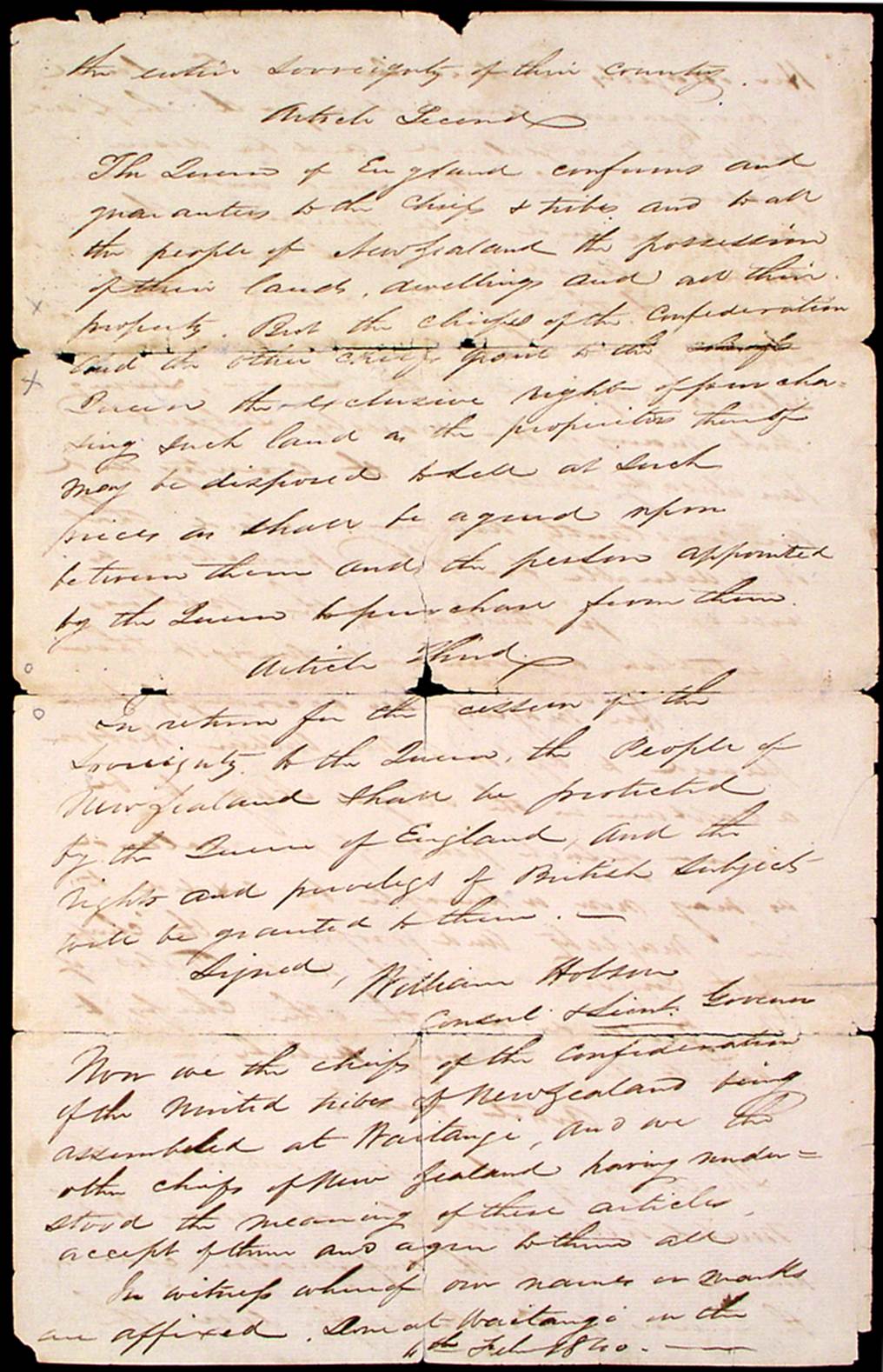

For the South Pacific country of New Zealand, the treaty entered into in 1840, between the British Government and Maori chiefs, provided the “permission slip” for the formation of a British colony. For this to occur, 540 chiefs across the length and breadth of New Zealand ceded their sovereignty to Queen Victoria, so that they could sit in the shadow of the Queen and be protected by Her.

The reason the chiefs chose this course of action, after careful deliberation and years of discussion within their tribes, included : fear of invasion by the French, a need to stop constant inter-tribal warfare and a strong desire for the much-needed institution of law & order.

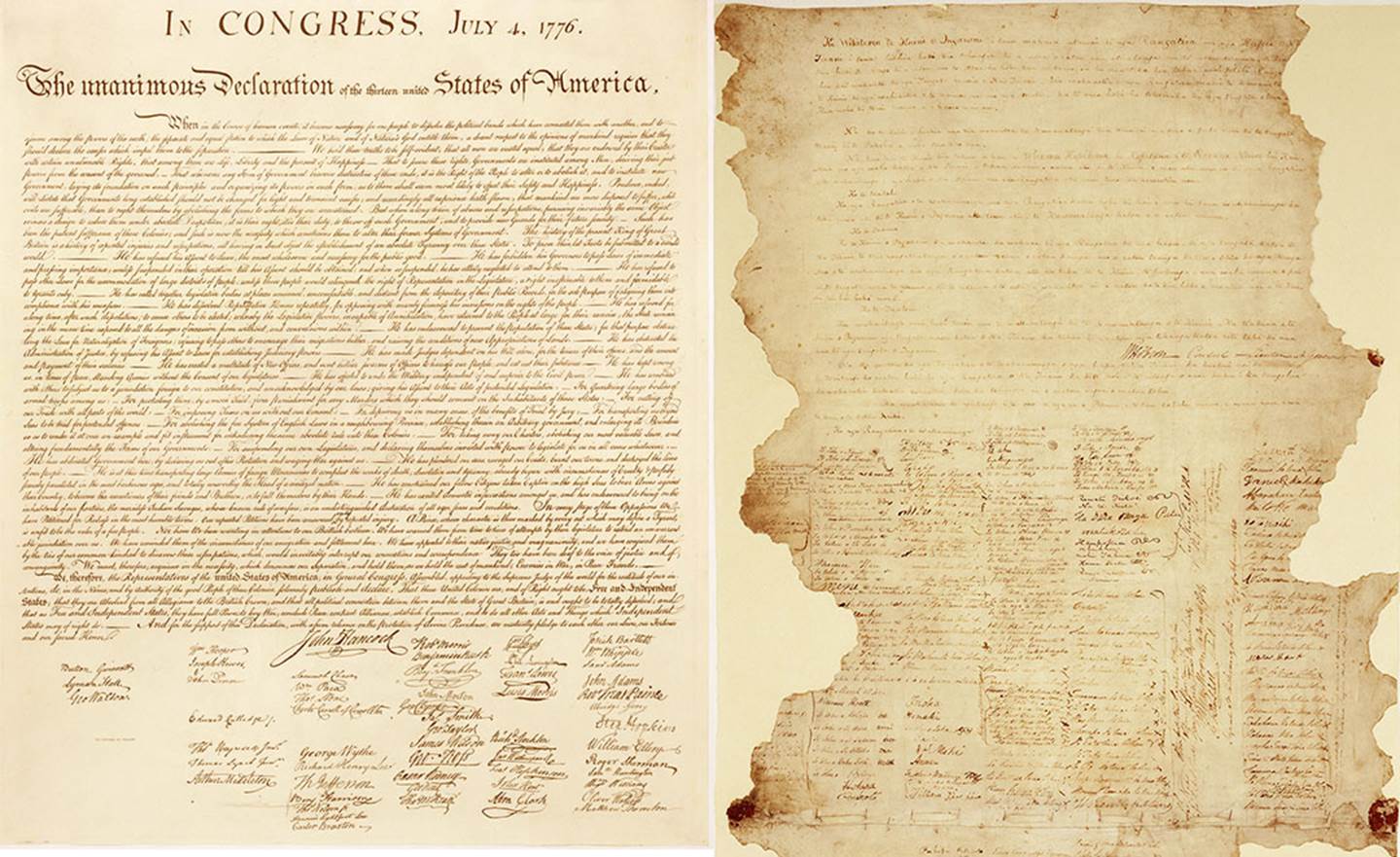

For the people of New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi was the equivalent of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, and their brilliant, follow-on Constitution & Bill of Rights that later defined how affairs were to be conducted within the newly formed Republic of the United States.

Both the New Zealand Treaty of Waitangi and the United States Declaration of Independence were the founding or preliminary documents of the two countries and both were drafted with great care over several days, with the participation and input of many learned individuals, in order to achieve the required clear and precise tenets, upon which successful, abundant and caring nations are launched into existence.

The United States of America Declaration of Independence sits alongside New Zealand’s Tiriti o Waitangi. Each represented beginning or foundation documents from which two new nations, each with a new direction, sovereignty and egalitarian laws came into being. Americans have had to be ever-vigilant, battling constantly against tyrannical forces in order to preserve the tenets and scope of their founding principles. New Zealanders lost that battle in the 1980s - 90s against the globalist forces.

In the case of New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi / Te Tiriti o Waitangi the final, defining, binding, legislative text was solely in the Maori language and this fact was affirmed by Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson, the British emissary sent to New Zealand to secure a treaty with the Maori chiefs.

New Zealanders would never have any problems with the Maori-language text, as it is benign, all-encompassing and guarantees equality under the law to all, with no special rights for one group over another. It was never a race-based text and, despite dissenting, modern-day views from certain self-interest groups, was a perfect translation of the Final English draft.

Americans would consider it abhorrent and repugnant to witness words, ideas, meanings or intents of their founding document being altered, and any such tampering would unleash such an angry hue & cry of protest from the common people that the meddling interlopers would have to swiftly back off.

And yet New Zealanders, up until 1975 and after 135-years of knowing what the Treaty of Waitangi truly meant, were increasingly led-to-believe (conned-into-thinking) that the Treaty of Waitangi had an altogether different meaning to that which many generations of New Zealanders, both Maori & European alike, had accepted as established, documented, historical fact.

Whereas Americans still have to be constantly vigilant and fight hard to preserve their rights under the US Constitution, New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi has, sadly, fallen victim to the guile of activists and their lawyers and has been severely crippled. The reinvention of meaning and subsequent erosion of rights has been ongoing and relentless during the past 50-years, wherein a benign, clear text of unification has been drastically transformed into a Maori-supremacist imposed formula for apartheid or separatism.

Here is a documented account of how most New Zealanders lost their inalienable rights guaranteed under the Articles of the Treaty of Waitangi:

Firstly, let’s review a well-known, ALL IMPORTANT historical fact from 1840, as well as an outstanding discovery that occurred 149-years later in 1989.

LOSS OF THE FINAL ENGLISH DRAFT, THE MOTHER DOCUMENT FROM WHICH TE TIRITI O WAITANGI WAS TRANSLATED.

It is openly acknowledged by our Treaty of Waitangi historians and experts that The Final English Draft of the treaty, which provided the text for the Maori translation, went missing sometime in February 1840.

From historical references and written testimonials of those directly involved, we know that the Final English Draft document was in the handwriting of British Resident, James Busby. Captain William Hobson (who later became New Zealand’s first Governor) handed the Final English draft to Reverend Henry Williams ‘at 4 p.m. on the 4th of February 1840’ for translation overnight into Te Tiriti O Waitangi (the Maori language text).

It was absolutely essential that the Maori chiefs heard, considered and fully understood the British proposal in their own language before deciding whether or not they would cede their sovereignty to Queen Victoria

In mid-March 1989 an English language version of the Treaty of Waitangi was found in Pukekohe, South Auckland, when members of the Littlewood family were sorting out the estate of their recently deceased mother, Ethel Littlewood.

DIRTY TRICK NUMBER 1 … WITHHOLDING INFORMATION FROM THE PUBLIC ABOUT THE FIND OF “THE FINAL ENGLISH DRAFT OF THE TREATY OF WAITANGI & ITS AUTHOR”.

When first found amongst Littlewood family papers, the old sheet was cracked along the fold lines and had, at some point, been cellotaped by a family member to hold it together in one piece.

This old sheet of paper has, subsequently, been identified to be in the handwriting of British Resident, James Busby by New Zealand’s leading handwriting expert of documents from the early colonial era, Dr. Phil Parkinson of the Alexander Turnbull Library. We know from historical records that the original “Final Draft” had to be in the handwriting of James Busby, as he acted as the secretary on the 4th of February 1840 when the Final Draft text was decided upon and created.

The New Zealand Government has continued to withhold the fact that James Busby is the author, as that would alert the public to the fact that the Final English Draft, the mother document of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, has been found.

An astounding feature of this newly found document is that it is dated the 4th of February 1840. It is also written on very old paper, bearing a W. Tucker 1833 watermark. The paper stock was owned by James Reddy Clendon, US Consul and the only individual in New Zealand ever known to have used that watermarked brand of English paper was Clendon.

John & Barbara Littlewood with the author in 2003 - 4 very graciously shared all of the information they had, photocopies of the “Littlewood Treaty” document, newspaper clippings, historical information, genealogy, and events surrounding the finding of the document amongst family papers in 1989, as well as placing it into the care of Archives New Zealand in September 1992. John passed away in November 2015 and Barbara a year later.

John Littlewood and his sister, Beryl were sorting through papers from their mother’s deceased estate in March 1989, when Beryl found the English language copy of the Treaty of Waitangi in an envelope marked, Treaty of Waitangi. There was a family tradition that John’s great-grandfather was somehow involved with the Treaty of Waitangi and, subsequent to the find, John spent two years trying to find out the significance and provenance of the document, before lodging it with Archives New Zealand.

Because of the due diligence of generations of the Littlewood family, the all-important fragile paper document was preserved. The New Zealand people owe the Littlewood family a debt of gratitude for their care & keeping safe of the most sought after, lost historical document of the colonial era.

WAS THIS THE MISSING FINAL ENGLISH DRAFT OF THE TREATY OF WAITANGI, LOST FOR 149-YEARS?

For over 150-years, when the document finally came back into the public arena (1992), generations of historians and politicians had been searching and "hoping against hope" that the "final English draft" of the treaty would finally and belatedly turn up. That it even survived is a miracle and a credit to the Littlewood family, whose consideration and respect, accorded to a fragile piece of paper, kept it safe, in their possession, for at least a hundred and thirty six years or longer.

As stated, James Busby is, positively and without dispute, the author of the Littlewood Treaty document. He's also the undisputed individual who penned the final English draft of the Treaty of Waitangi on the 4th of February, 1840.

For over 150-years before the Littlewood document came to public attention in 1992, we had been looking for a piece of paper with the following attributes:

One would have to scratch one's heads in bewilderment...if this document doesn't satisfy our mainstream historians as the elusive and long sought after final English draft, under all of the clinically stringent, qualifying criteria, then what ever would or could satisfy them?

In view of the weight of evidence supporting the document's authenticity as the final draft, one would have to conclude that it is, simply, not considered politically convenient or expedient to recognise it for what it truly is and that factor, undoubtedly, constitutes the real underlying issue.

It's also significant that the New Zealand Government has never allowed for a general release of photographs of the document. The Littlewood family had to be supplied with with black & white, poor quality photocopies, but the colour photos in circulation had to be acquired by more back-door methods and then leaked into the public arena against the wishes of the authorities.

During late 1992 and for years thereafter those asking for photographs were refused on the basis that the document was "too fragile", even though it had undergone preservation and had already been photographed in high resolution by Preservation Services at the New Zealand National Archives.

It was also misrepresented as a "back-translation" from the Maori language text, even though its signed-off, date (the 4th of February 1840) showed it had been written before there was a Maori language translation (the 5th of February 1840).

In this matter our historians and forensic scientists are seriously derelict in their duty to the people of New Zealand and three decades of deliberate foot-dragging, silence, misrepresentation, misinformation or pretending that the document does not exist, shows the contempt state-employees have for the public who pay their wages.

It's a simple and innocent enough task to tell the public officially the full, forensic status of the document, who wrote it and what is the true significance of the date on it ... or is that somehow inconvenient and counterproductive to a preferred agenda?

By the 1850’s, at least, James Reddy Clendon, Police Magistrate, was using Littlewood’s legal services for conveyance work and this explains how solicitor, Henry Littlewood, gained possession of the Final English Draft of the treaty.

The records of Surveyor-General, Felton Mathew would suggest that James Reddy Clendon was issued the Final English Draft of the Treaty of Waitangi, on or about the 13th of March 1840. Unfortunately, Clendon never returned the document to the New Zealand Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, but retained it for many years until lodging it with his solicitor, Henry Littlewood.

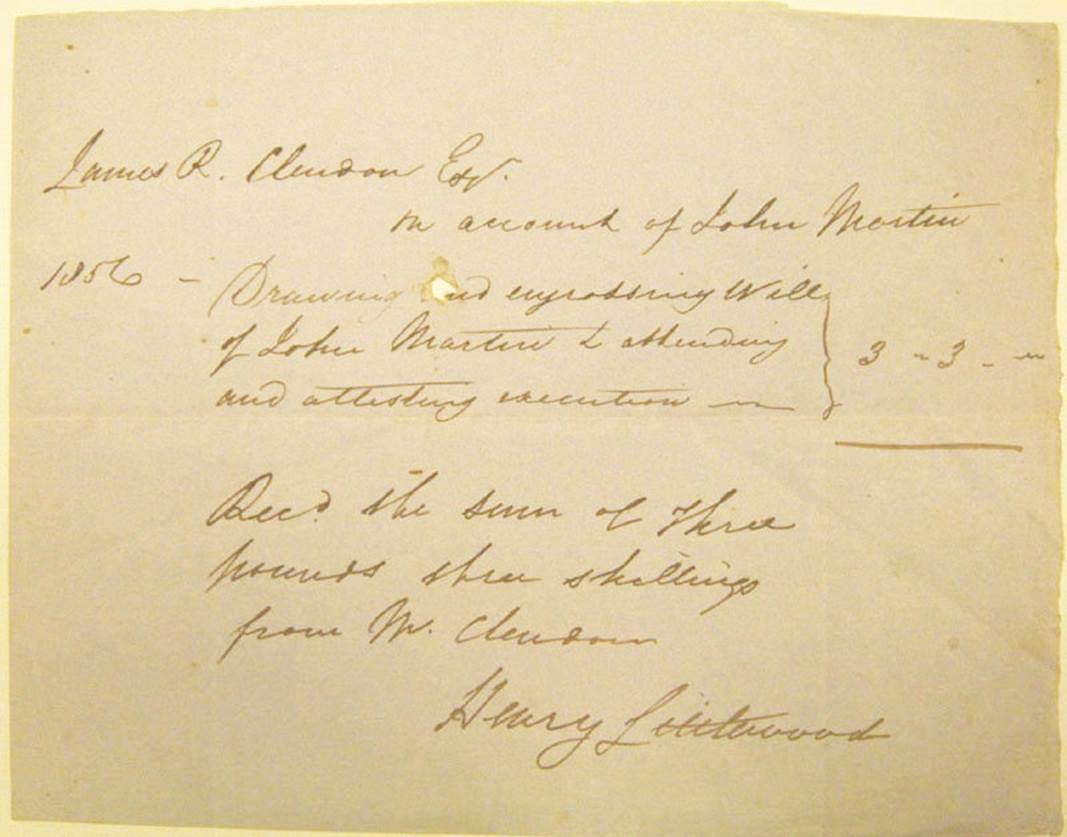

A receipt issued in 1856 by solicitor Henry Littlewood, John & Beryl Littlewood’s great-grandfather, to James Reddy Clendon, for conveyancing work related to the will of John Martin. In 1839 through to 1841 Clendon, in residence at the Bay of Islands, had been appointed by the United States Government to act as their Consul. He was to report on the comings & goings of US whaling ships, as well as any significant events, such as annexation of New Zealand by the British Crown as a colony.

We now know from historical documents that Clendon had been loaned the English language Final Draft original by Lieutenant Governor William Hobson, upon Clendon’s official request to the Colonial Secretary. It had been forwarded to Clendon in his official capacity as U.S. Consul.

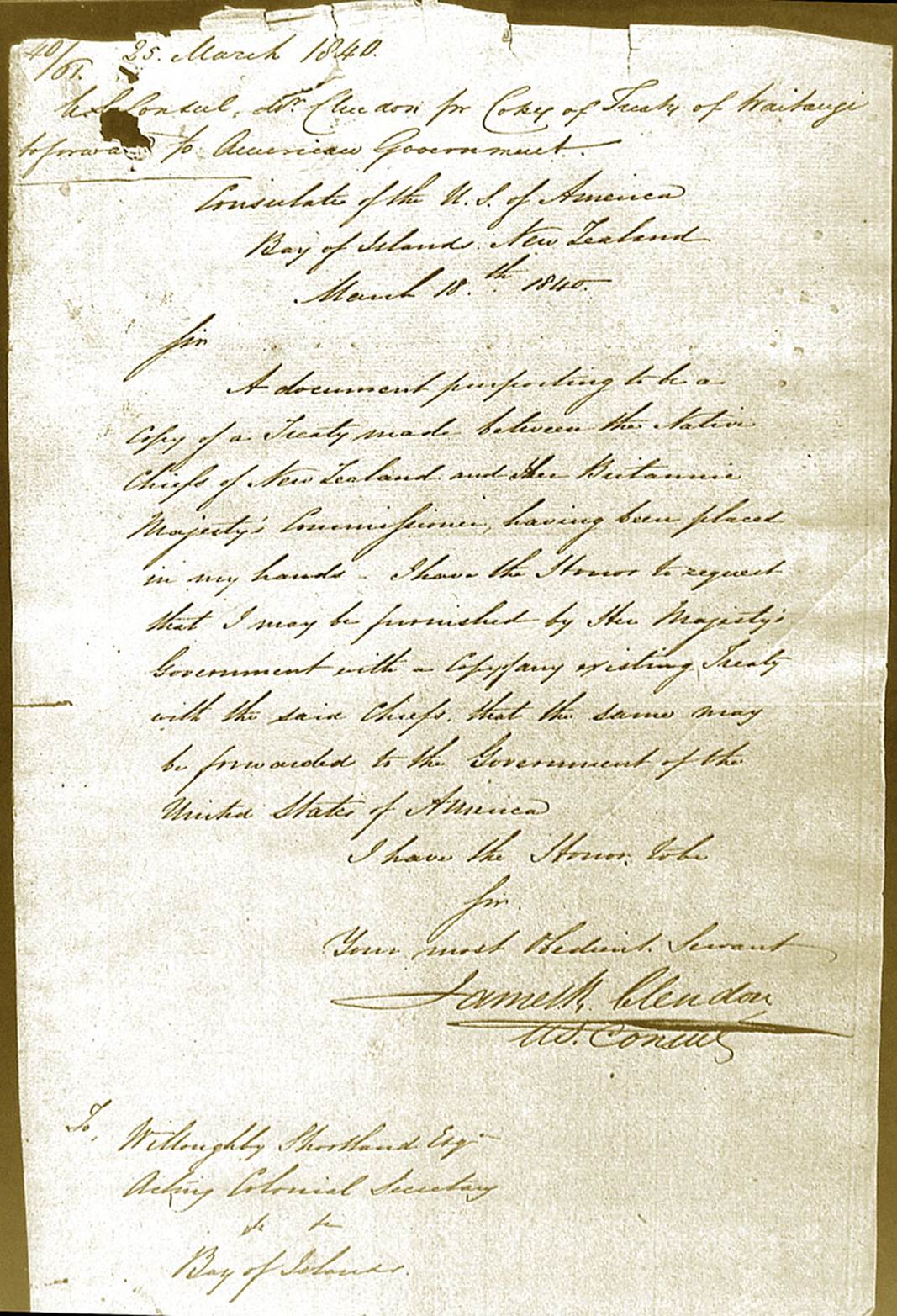

Clendon even issued a receipt on the 25th of March 1840, stating he had received the Treaty-related documents requested, supplied in both the Maori and English languages, which he needed to forward to John Forsyth, US Secretary of State in Washington DC.

The handwritten, Maori language copy, issued by the official translator, Reverend Henry Williams, is still found within the Clendon House papers, Auckland Public Library Special Collections. Clendon's transcribed copy in English is in the US National Archives, Washington DC and can be seen on microfilm (See: Auckland Institute and Museum Library: Micro # 51. Despatches from the U.S. Consul to the Bay of Islands and Auckland, 1839-1906: Roll 1, May 27, 1839 - Nov. 30, 1846, also available at the University of Auckland Library).

Because the Maori chiefs at The Bay of Islands had decided to cede sovereignty to Queen Victoria and form a British colony, US Consul Clendon was obliged to inform his superiors in Washington DC and needed the Treaty-related documents. These were supplied in both the Maori and English languages under an official consular request made by Clendon to the newly formed New Zealand colonial government.

In the above receipt to the NZ Colonial Secretary he acknowledges receiving the items requested, which included the Final Draft English text. The same two language texts were supplied by Clendon to US Antarctic explorer, Commodore Charles Wilkes and recorded as despatched materials in the USS Vincennes letter book, as well as being sent to the USA, again, in Wilkes’ Despatch 64 enclosure to his superiors.

Compelling paper-trail evidence would lend credence to the fact that the document, which in recent years has been dubbed the "Littlewood Treaty" by our historians, was the same English language treaty document supplied to James Reddy Clendon by the Hobson government, in fulfilment of an official consular request, on or about the 13th of March 1840.

We know that Surveyor General, Felton Mathew, in company with James Stuart Freeman, Hobson's private secretary, visited Clendon on the 11th of March 1840, five days after H.M.S Herald arrived back at the bay with a paralysed Hobson on board. Something, quite apart from discussions about purchase of Clendon's Okiato estate by the government, compelled Felton Mathew to return to Clendon on the 13th of March 1840, with whom he had "some business" to conduct.

In this instance he doesn't appear to have done any further exploratory work on the property, as he and Freeman had done two days before, but left there to go and visit the American Schooner, Flying Fish to "chat" with the Captain and Lieutenant, returning to the Colonial Secretary's cottage at Kororareka at dusk.

It's significant that Clendon had officially requested complete treaty documentation from the Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, who had remained at the Bay while other members of Hobson's staff (and including Reverend Henry Williams) had been away to the Thames between February 21st and March 6th 1840 aboard H.M.S. Herald.

When H.M.S. Herald left for Australia on the 12th of March, both Felton Mathew and James Stuart Freeman moved in to live with Shortland at the two-room cottage at Kororareka, It's plausible to assume that in the interim day since Mathew's last visit to Clendon, Shortland had taken out of records the final English draft that Hobson had read at Waitangi and carried with him to the other venues, including to the Thames (Hauraki Gulf, Auckland Isthmus). This "final English draft" was to be given to United States Consul, James Reddy Clendon in response to his formal consular request to the New Zealand Government.

Alternatively, Reverend Henry Williams would, most assuredly, have attended with the others to wish the Herald "bon voyage" to HMS Herald on the 12th and Williams could well have made Clendon's requested "official Maori" copy available on that day for delivery by Felton Mathew to Clendon on the morrow.

Although the "official" or "final draft English text" would, ultimately, be sent in Wilkes' despatch No. 64 a little over two weeks later, it makes sense to assume that Clendon, at that moment, intended to send it with the US vessell, The Flying Fish, one of the ships of Captain Wilkes' scattered and battered squadron, fresh from exploring the "icy land" of Antarctica. It was in the bay at the time undergoing repairs.

At that time, Clendon had no idea that Wilkes', aboard the U.S.S. Vincennes, (squadron flagship), would sail into the bay on the 29th of the month to find his lost ships.

Felton Mathew had also been obliged to go to see Reverend Henry Williams at Paihia on the 10th of March 1840, 'for the purpose of transacting a little business', after which he returned to the Herald in the dark. Felton Mathew appears to have acted as a primary messenger during this chaotic time for the government, with Hobson paralysed, and Shortland having had a "falling out" with Cooper.

The main point is:

There is clearly recorded interaction between Felton Mathew, Reverend Henry Williams, James Stuart Freeman, Willoughby Shortland and James Reddy Clendon during the second week of March 1840, when James Reddy Clendon had his consular request to the government fulfilled and satisfied.

In his despatch No. 6, sent on the 20th of February 1840, U.S. Consul Clendon had promised the U.S. Secretary of State, John Forsyth, that:

'when Captain Hobson returns from the Southward', Clendon would 'apply officially' for the correct English and Maori texts of the treaty to be supplied 'for the purpose of sending it to the Government of the United States'.

We know that Clendon received what he had officially requested before the 18th of March 1840. Circumstantial evidence would suggest that on the 13th of March 1840, Felton Mathew, a senior member of Hobson's staff, gave Clendon both the "final English draft" (the Littlewood Treaty) and a "True Copy" of the Maori Treaty, hand-written by Reverend Henry Williams, the British colonial government's designated translator.

This pristine Maori language document is officially signed off by James Stuart Freeman, in behalf of the government and still survives amidst the Clendon House Papers at Special Collections, Auckland Public Library.

On the 4th of February 1840, James Busby was acting as secretary in composing the Final English language draft of the treaty. He said this himself in July 1861 (See: Appendix to Journals, E, no. 2, pg. 67).

The only plausible conclusion is that the final English draft (the Littlewood Treaty), dated the 4th of February 1840 was given to Clendon on or about the 13th of March by Felton Mathew to complete the "requested" set of both official Maori and English texts (See: The Unpublished Letters of Felton Mathew to Sarah Mathew, Special Collections, Auckland Public Library).

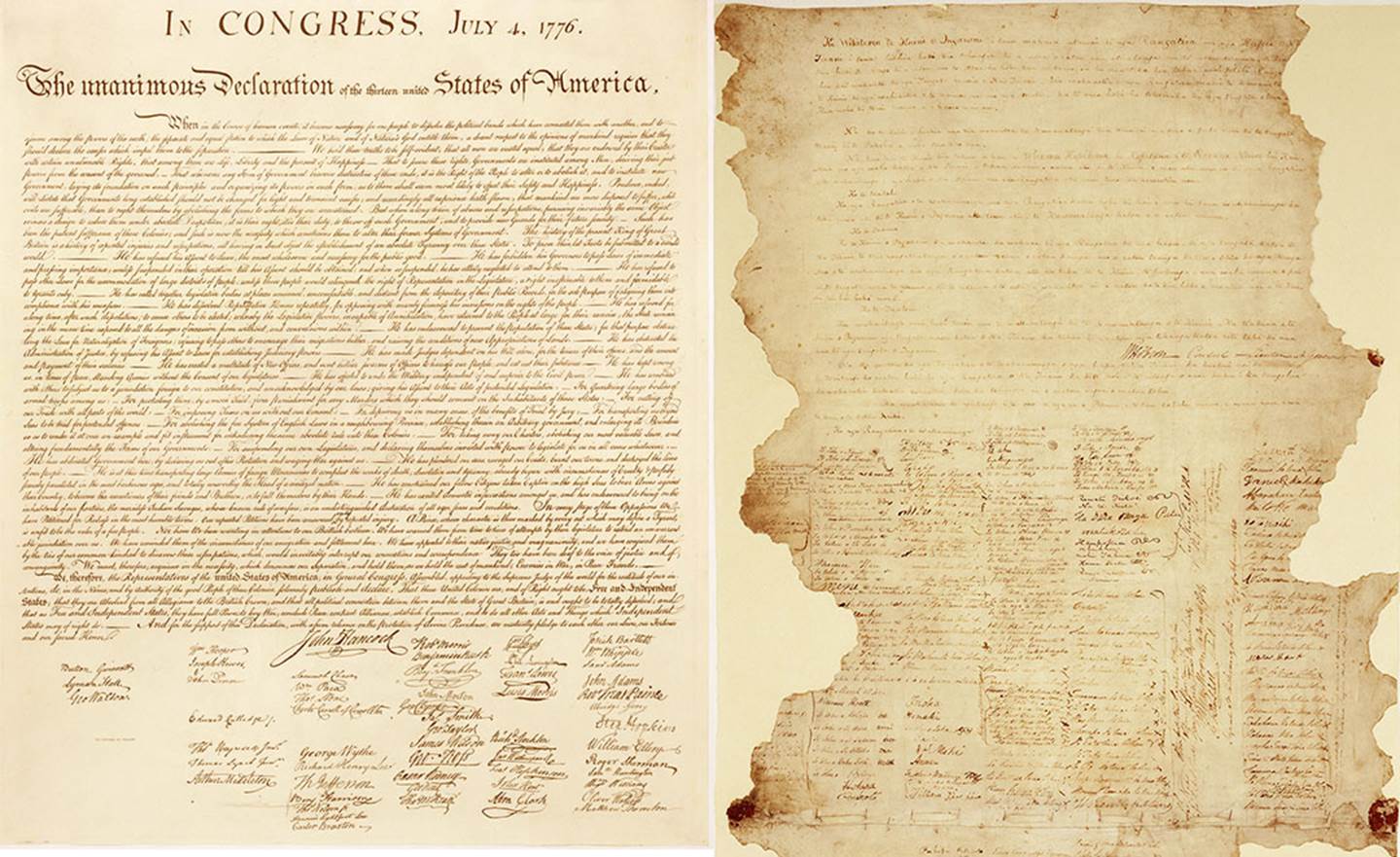

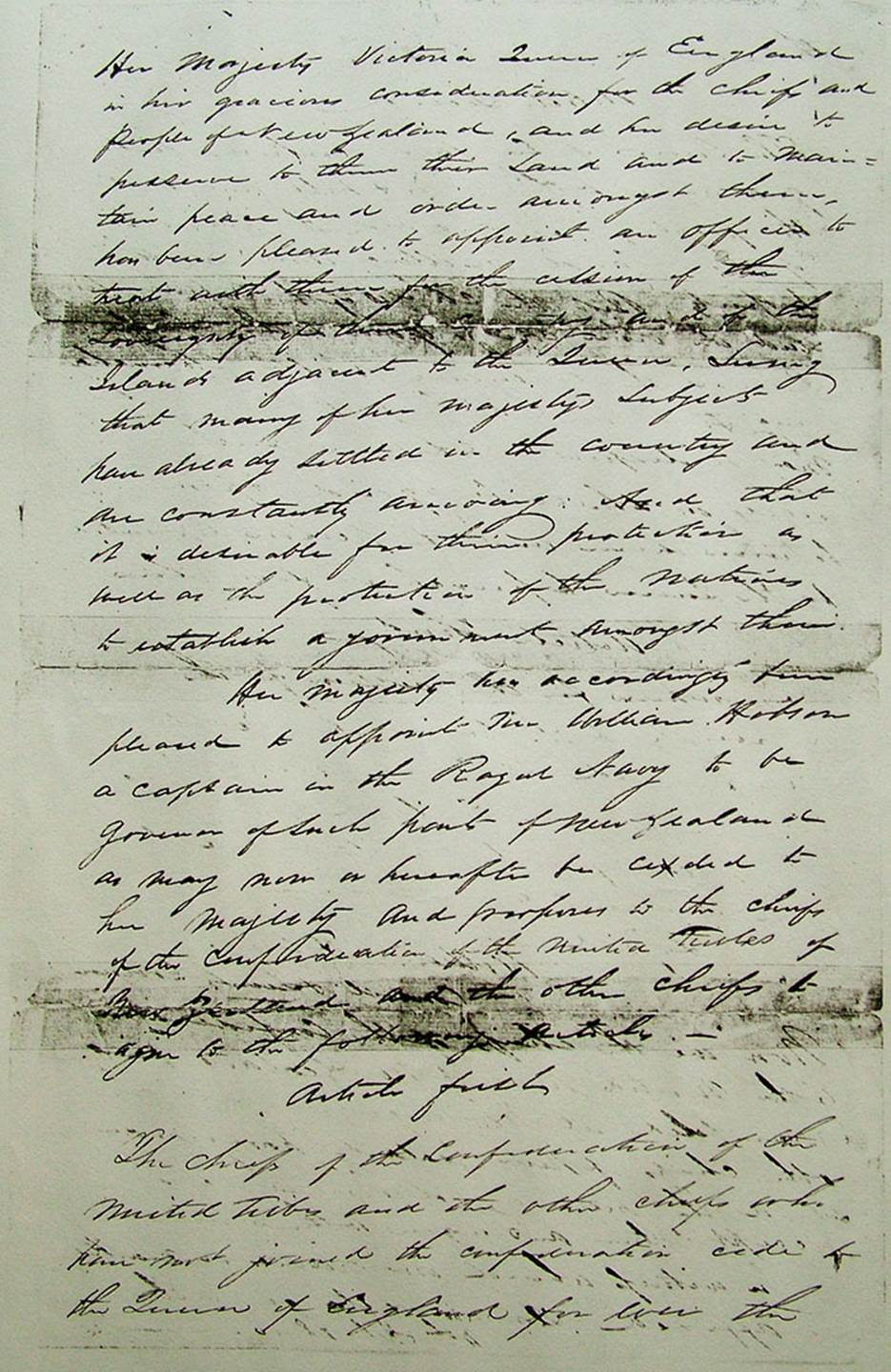

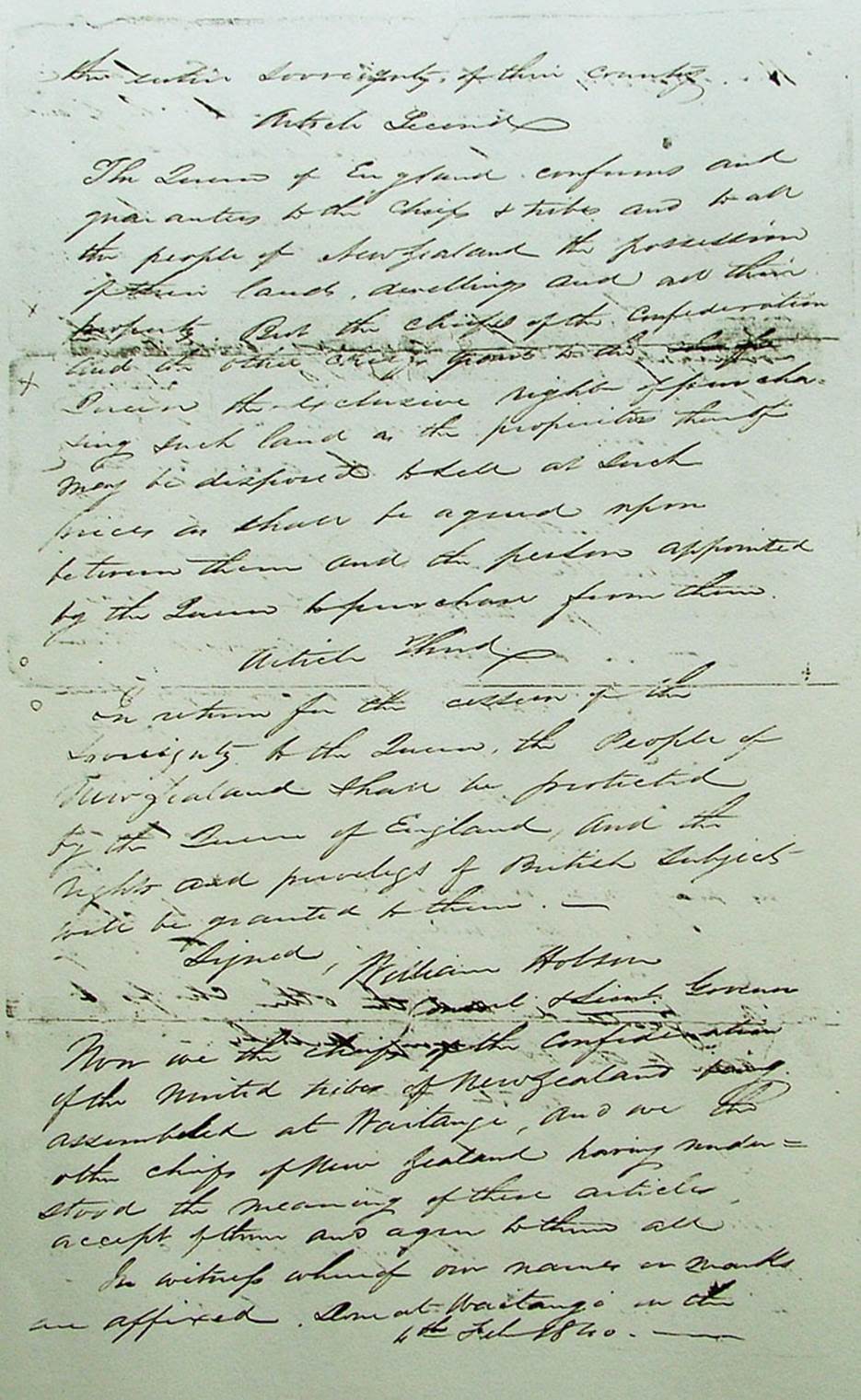

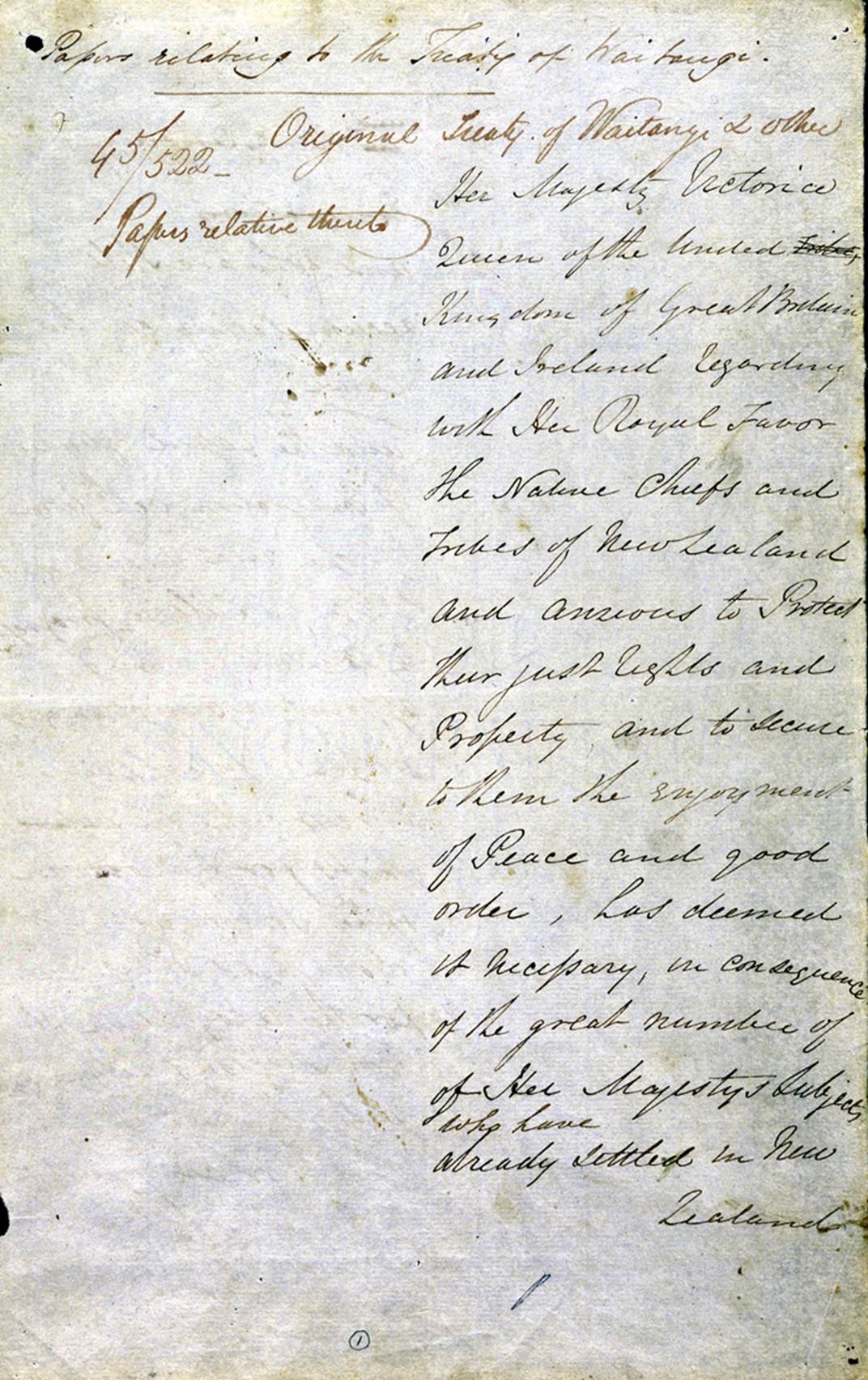

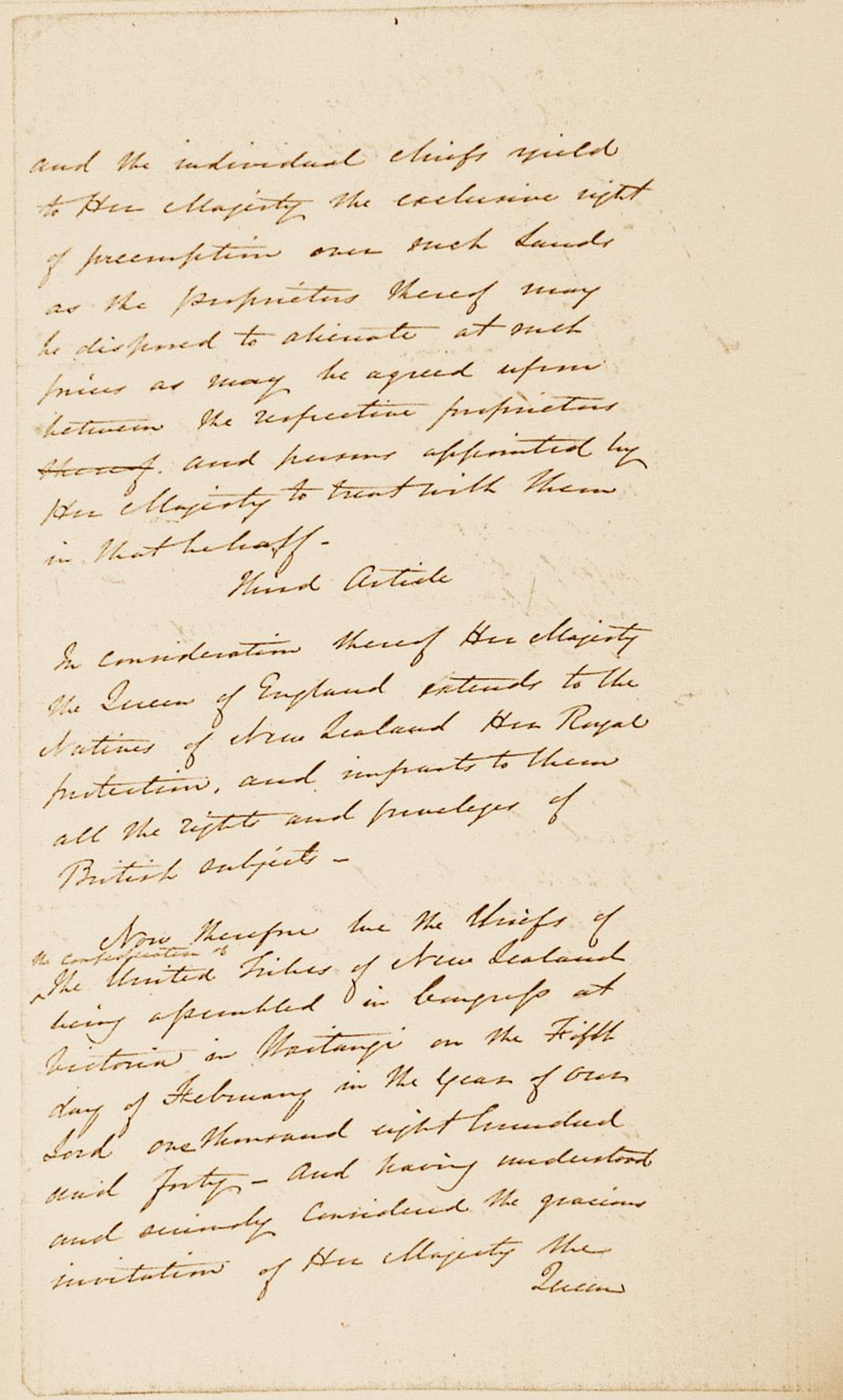

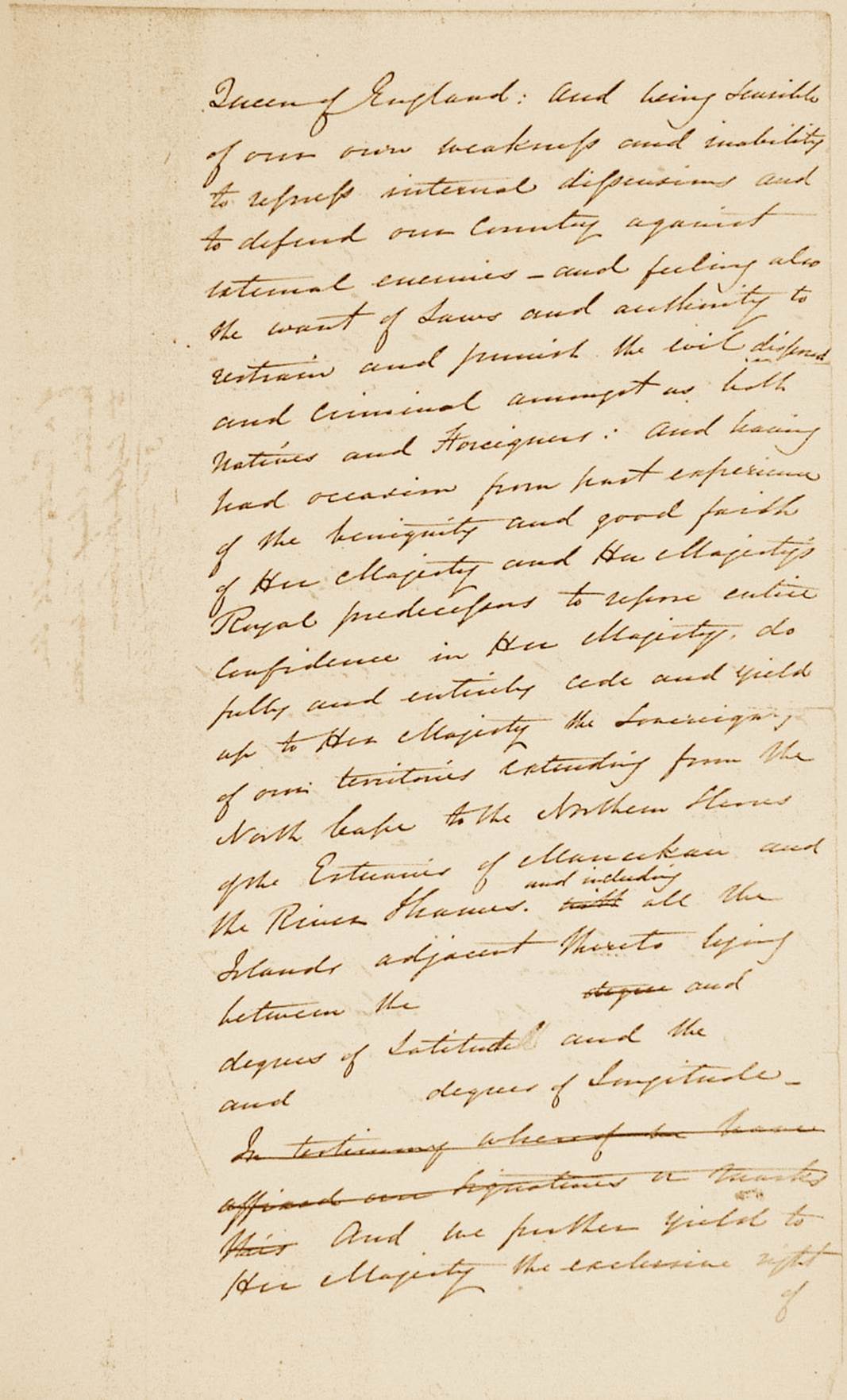

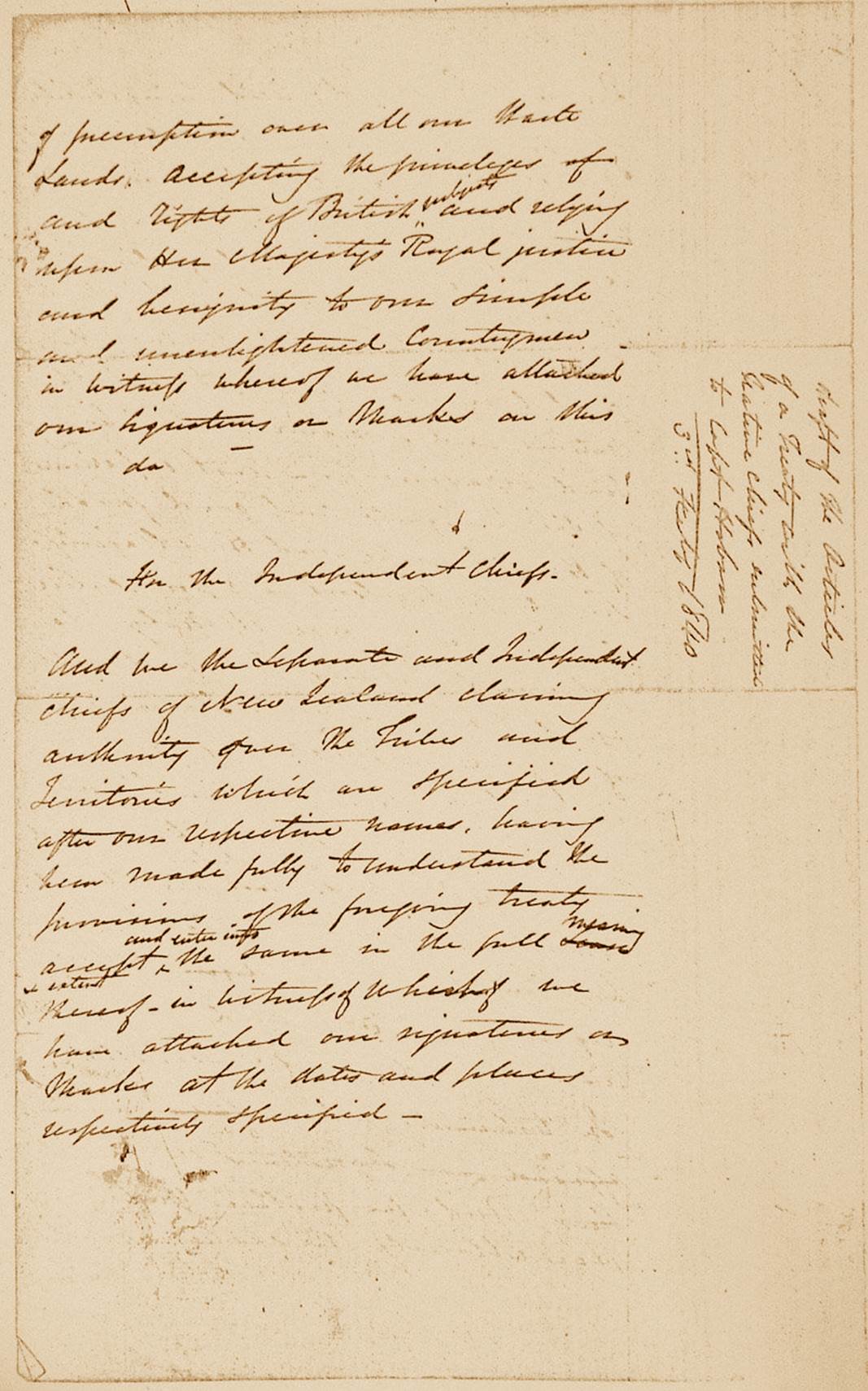

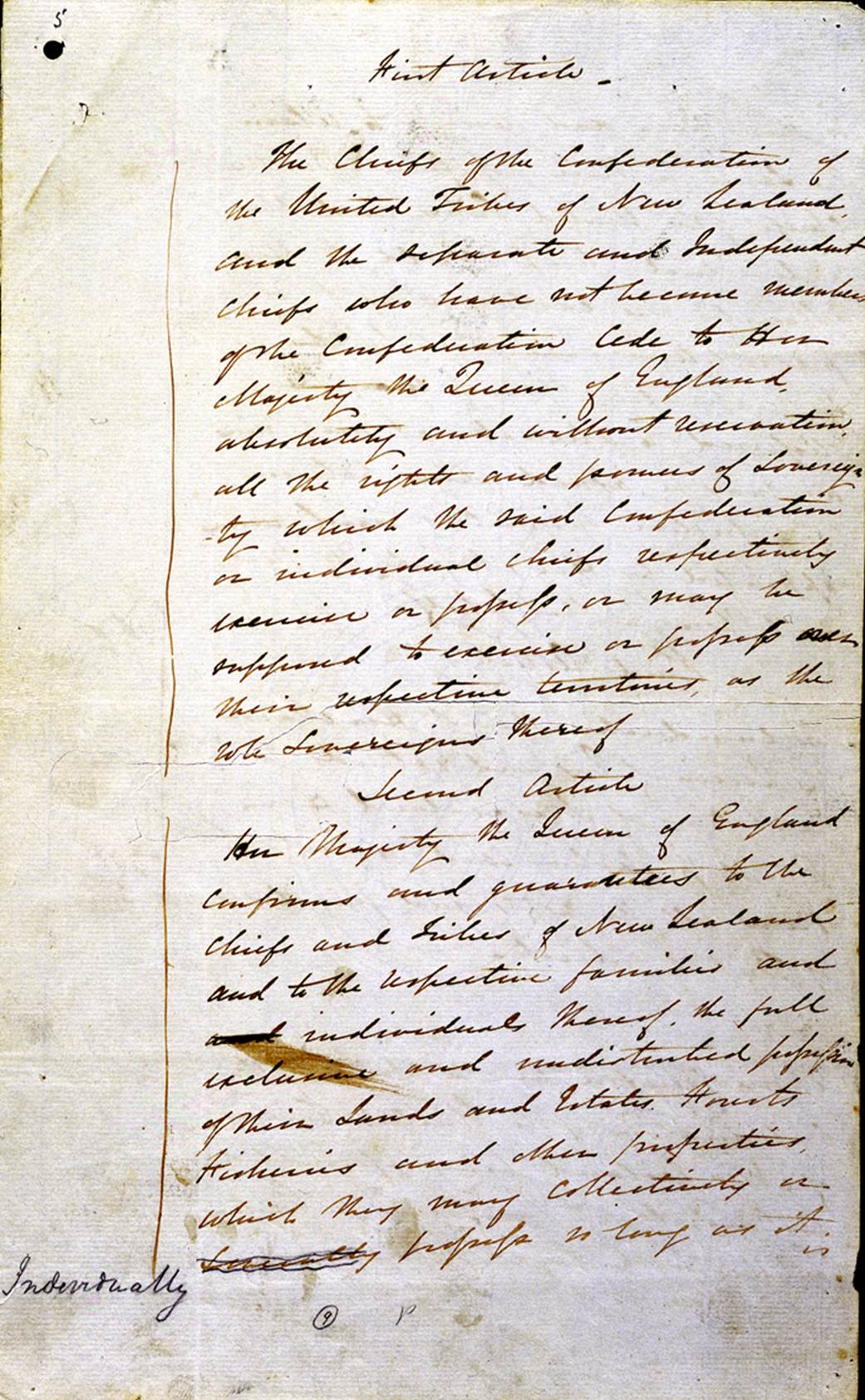

Here is the Final English Draft text penned by Busby, which was sent to Clendon by Hobson's government. It is seen sitting alongside its transcribed copy, penned by Commodore Charles Wilkes on April 3rd, 1840:

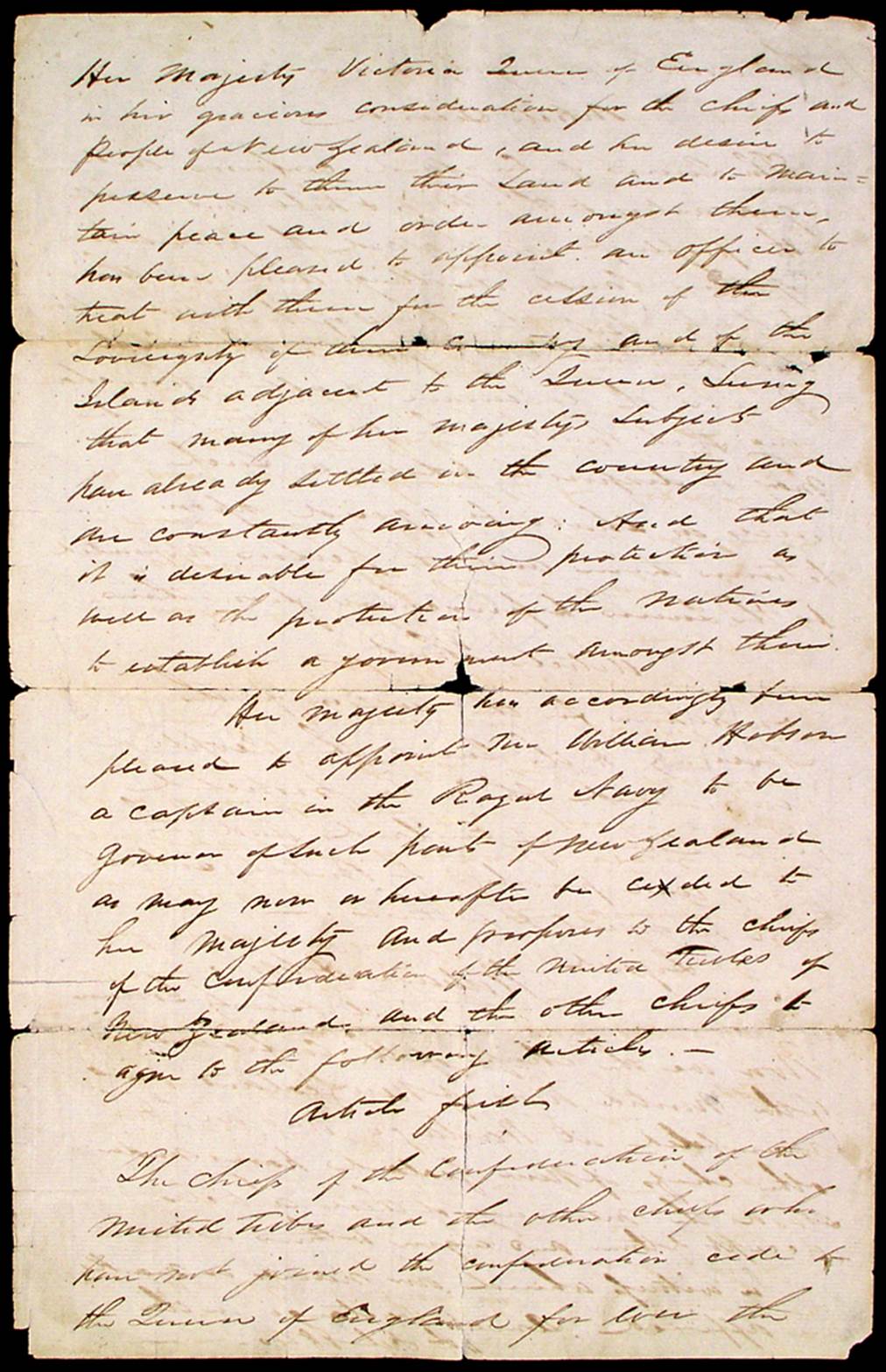

BUSBY’S FINAL DRAFT …4th of February 1840 Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of England in Her gracious consideration for the chiefs and people of New Zealand, and her desire to preserve to them their land and to maintain peace and order amongst them, has been pleased to appoint an officer to treat with them for the cession of the Sovreignty of their country and of the islands adjacent to the Queen. Seeing that many of Her Majesty’s subjects have already settled in the country and are constantly arriving; And that it is desirable for their protection as well as the protection of the natives to establish a government amongst them. |

WILKES’ DESPATCH 64 TREATY ... 3rd of April 1840. |

It can be readily seen that Busby's final English draft of the 4th of February 1840 was available to Commodore Charles Wilkes when he transcribed the text on the 3rd of April 1840 at James Reddy Clendon's premises. Although the transcript shows the Commodore has been a bit inattentive or hurried and left out "of the Sovreignty" in the Preamble, or has abbreviated some words, the text is the same. Wilkes has even copied Busby's spelling mistake for "Sovreignty" on two occasions, leaving out the tell-tale "e". Wilkes has also copied Busby's mistake where he wrote chiefs then crossed it out and inserted Queen. (See Papers of Charles Wilkes 1837-1847, despatch Number 64, Microfilm 1262, University of Auckland Library pp. 142-145 & 163-168).

James Reddy Clendon had also sent Busby’s Final English Draft text to John Forsyth, US Secretary of State, on the 20th of February 1840. He had a transcribed copy in his own handwriting from the 4th of February 1840 at his Okiato, Bay of Islands mansion, where the Final English Draft was completed under the direction of Captain William Hobson. Clendon was, however, unsure if it had undergone changes before, during or after the treaty assembly of the 5th of February.

Hobson had sailed southwards to attend a treaty assembly at Tamaki, Hauraki Gulf, Auckland Isthmus. Clendon awaited the return of (now) Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson to verify that the official English text remained the same as what he had himself transcribed on the 4th of February at his home and on his personal W Tucker 1833 watermarked paper stock. Clendon would have been cognisant of the possibility that translator, Reverend Henry Williams, might have wanted some English text changed in order to render a more precise translation. He also knew that a disruptive outburst by Catholic Bishop Pompallier, at the treaty assembly, calling for guarantees of religious freedom, might have led to an additional Article being added to the existing 3 Articles.

In the interim he sent the English text he had personally transcribed to John Forsyth in Despatch no 6 on the 20th of February 1840, and, upon Hobson’s return, was able to verify the original Final English Draft wording had not changed.

BUSBY’S FINAL DRAFT …4th of February 1840 |

CLENDON’S DESPATCH... 20th of February 1840 |

It can be seen that the English language treaty text Clendon sent to John Forsyth, US Secretary of State in Washington DC, is exactly the same, word-for-word, as the text found by the Littlewood family in 1989. Clendon has been astute in not misspelling the words sovereignty or ceded, has eliminated the crossed-out word chiefs and has added capitalisation where he deemed it appropriate, otherwise the two renditions duplicate each other perfectly.

It is absolutely proven beyond doubt that the exact piece of paper, bearing a Treaty of Waitangi text in English found by the Littlewood family in 1989, was in the hands of Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson, James Reddy Clendon and Commodore Charles Wilkes, respectively, in February, March & April 1840 and transcribed copies of that text still languish in the National Archives of the United States of America.

After over two years of trying to ascertain the significance of the 1989 find, John Littlewood contacted treaty historian, Claudia Orange, who came to his home to see the document. Her first reaction was to state that this ‘could be the lost final draft that went missing in February 1840’. She later convinced the Littlewoods that it should be lodged, with some urgency, into the care & keeping of the New Zealand National Archives, Wellington.

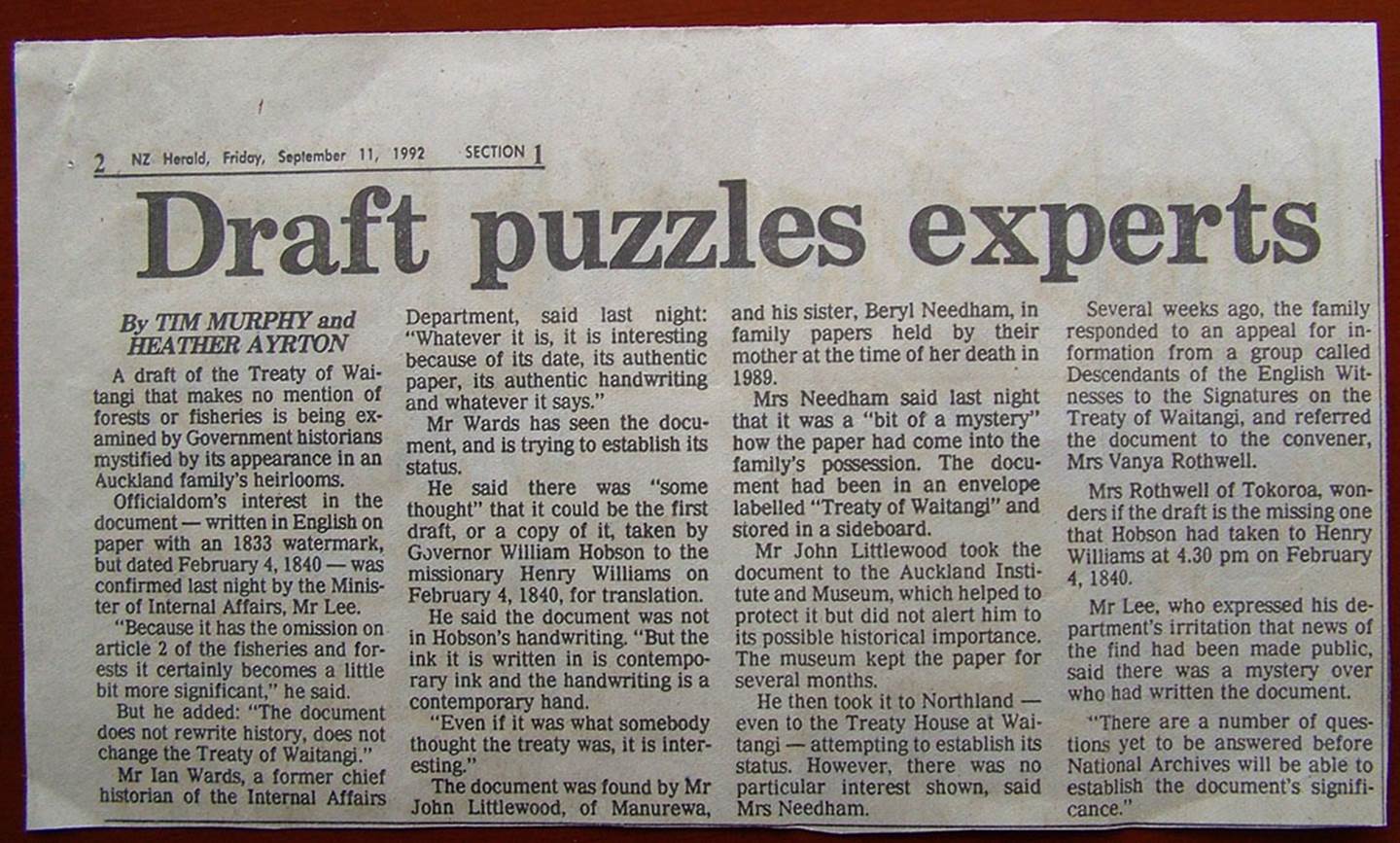

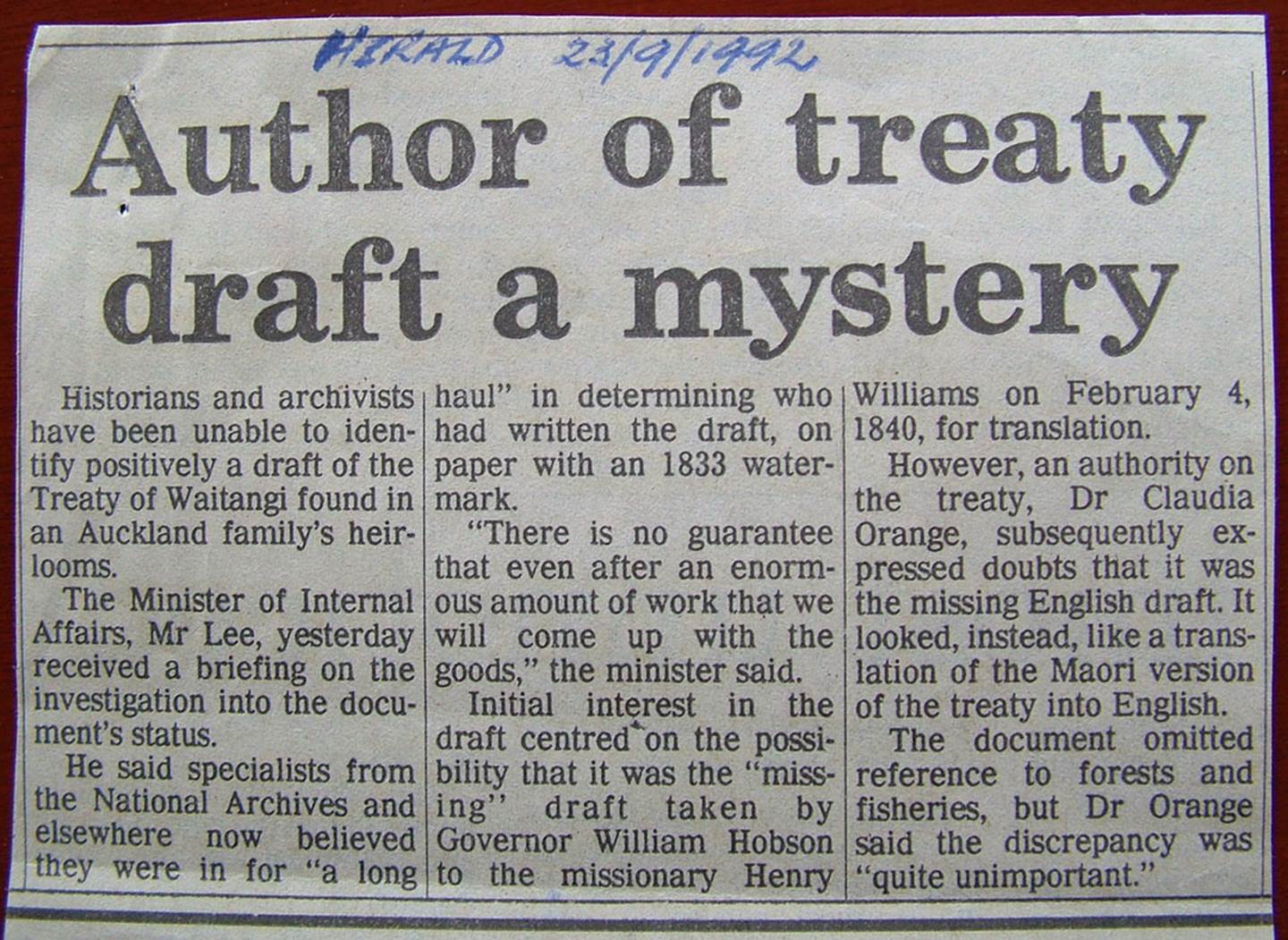

This was done in September 1992, but news of the find was supposed to be withheld from the public. However, a “whistle-blower” in archives alerted the newspapers, much to the chagrin and “irritation” of Minister of Internal Affairs, Mr Lee.

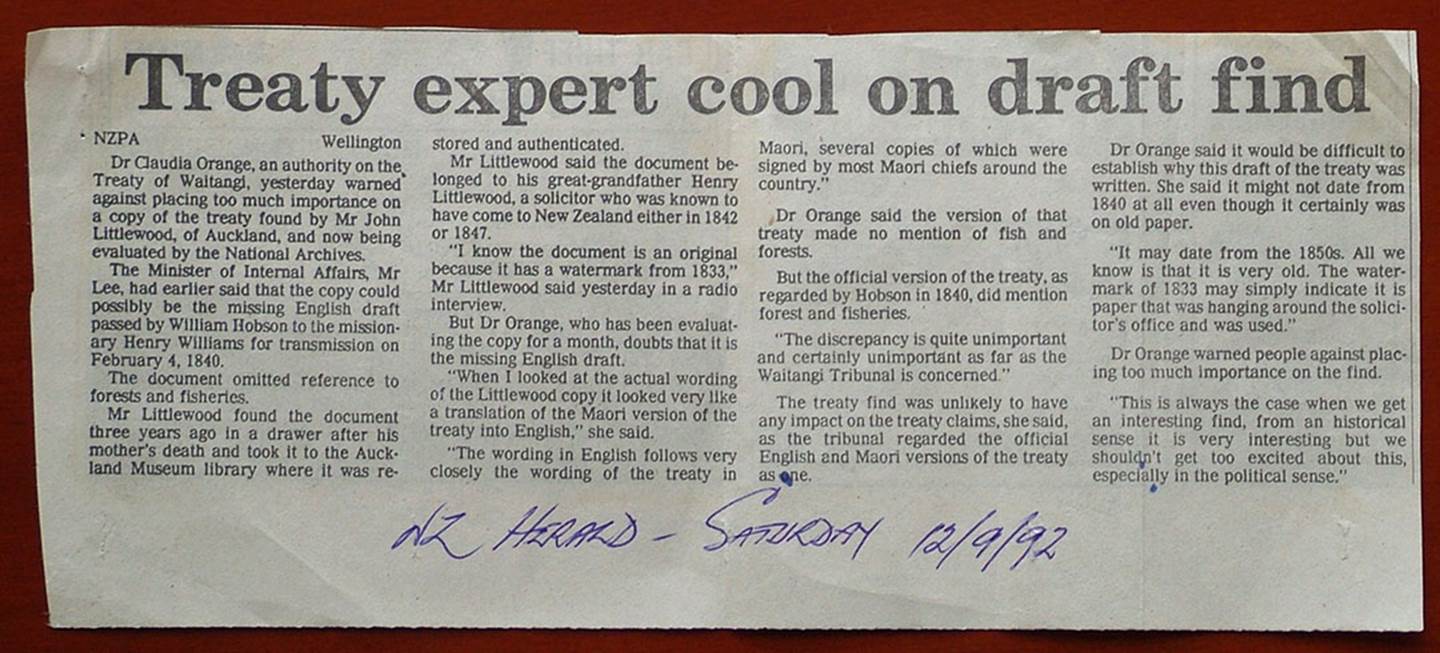

One of several newspaper articles about the Littlewood family’s document find, after a whistle-blower in archives leaked knowledge of the discovery to the media in 1992. Despite an initial burst of strong speculation that it was the "lost" final English draft, the media and our historians went very silent on the subject thereafter and promises to the public of a full forensic analysis were never honoured. This discovery constituted "a most unwelcome find" to the Maori grievance-industry and had to be buried at all cost.

Here are yet other newspaper articles mentioning the newly found, English language treaty document:

In this article, the “leaked” treaty document, that was never intended to be seen by the general public, is being down-played as to its importance or provenance. Whereas, identifying the person who hand-wrote it was extremely easy, that all-important information did not leak into the public arena for another 11-years.

By this time in late 1992, the meaning of the Treaty of Waitangi had been subjected to more than a decade of radical reinterpretation to make it support the political agenda of Maori supremacists, Marxist agendas and justification for multi-national corporation resource-plundering of New Zealand. This discovery of what would be, many years later, proven forensically to be the true Final English Draft had to be down-played and social-engineer historians were brought in to dissuade the public from learning the real significance of the document find.

In October 2003 I commenced in-depth research into the provenance of this suppressed and effectively all-but-forgotten document, spanning two years of investigation. During the period I had multiple interviews with the Littlewood family discoverers and spent considerable time seeking out many rare documents housed at multiple archives, libraries, within private collections or on microfilm, locatable at resource centres around New Zealand, Australia, Great Britain and the United States.

The outcome of this exercise was that I was able to prove, conclusively, that the Littlewood-discovered document was, beyond any doubt, the much sought-after Final English Draft and mother document of the Treaty of Waitangi, from which the Maori language Tiriti o Waitangi was translated.

As a consequence of this fact, the recent-era treaty revisionism, or reinvention of the Treaty of Waitangi since 1975, was proven to be founded upon transparent fraud, as well as unscholarly make-believe and wishful-thinking. The very socially destructive ruse of deliberate misinterpretations of the treaty was pushed and promoted by self-serving Maori activists and their cohorts for monetary or political gain, etc. It had no basis in true history, as attested to by the paper-trail of historical documents.

The newly available information was compiled into a book, titled, The Littlewood Treaty - The True English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi Found, 2005, ISBN 0-437-10140-8. The book, complete with rare documents, is available online at:

http://www.celticnz.org/TreatyBook/Precis.htm

The emergence of this fully documented history into the public arena was very threatening to the lucrative grievance-industry and sent ripples of panic throughout their ranks, resulting in the implementation of damage-control incentives, comprised of re-education or indoctrination programmes like the very expensive Treaty-2-U traveling propaganda roadshow unleashed upon our "bussed-in" schoolchildren during 2006 - 2007.

http://www.treatyofwaitangi.net.nz/Treaty2UPart1.htm

In the aftermath, a gaggle of social-historians, ushered in to do damage-control, were given the impossible task of debunking the new, documented information and were assigned the dubious role to be the great "Defenders of the Faith".

THE ONGOING MEDIA CLAMPDOWN & CENSORSHIP IN SAYING OR WRITING THE TITLE “LITTLEWOOD TREATY’.

After knowledge of the existence of the Littlewood Treaty document emerged back into public focus in the December 2003 - January 2004 issue of Investigate Magazine, Ian Wishart, editor and talk show host, stated on air that his media colleagues had told him there was a general media ban on saying the words, “Littlewood Treaty”.

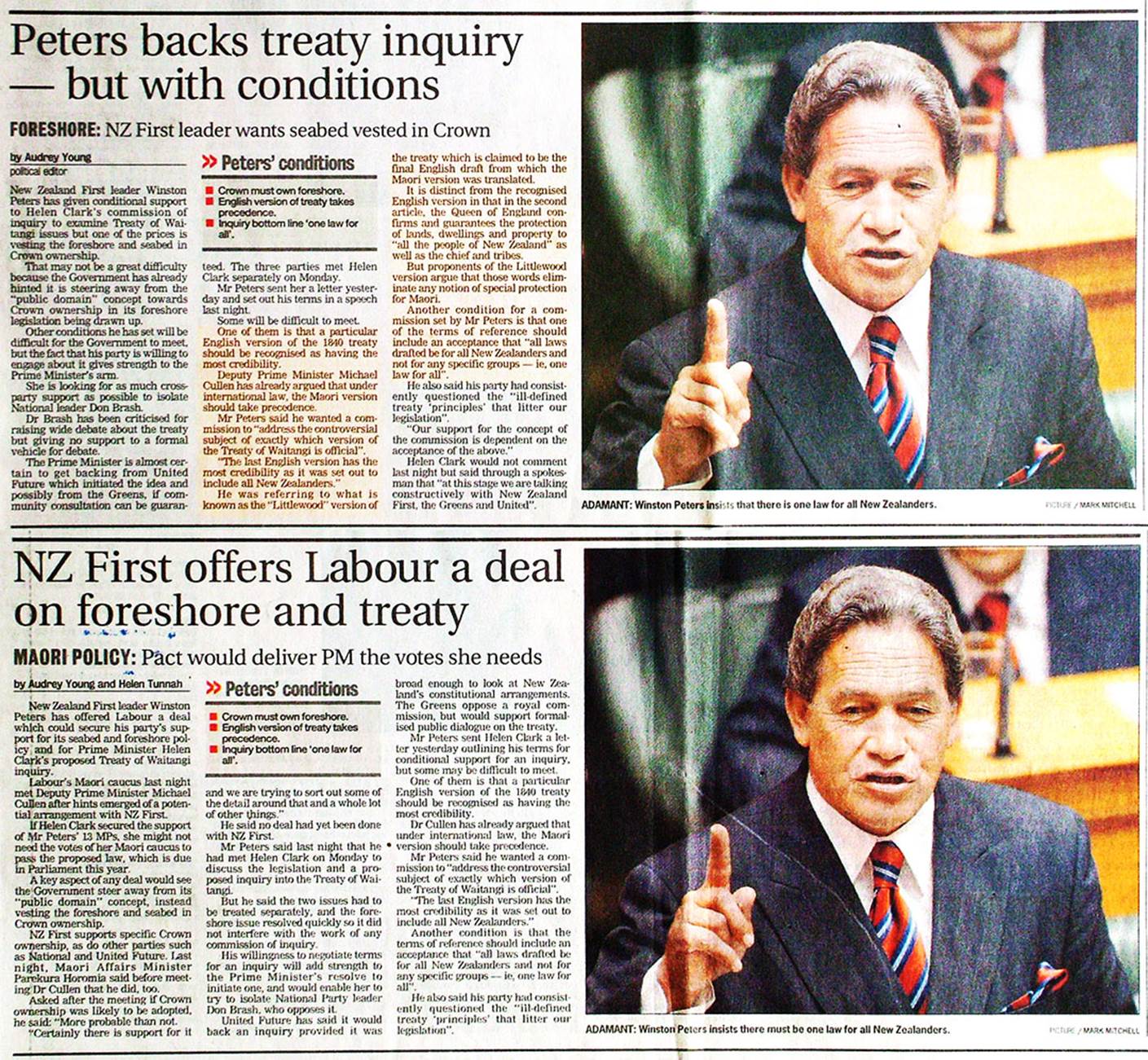

Despite this, on the 18th of March 2004 one journalist, Audrey Young, quoted directly from a speech by the Hon. Winston Peters and qualified his statements to show he was talking about the “Littlewood Treaty”. This text went out in an early Herald edition to the Bay of Plenty. The offending “Littlewood Treaty” text was, it seems, discovered by censors and quickly eliminated before the next printed edition.

The two articles (early and later editions) remained exactly the same physical size and general layout, except for the later edition’s exclusion of the 3 instances when the “Littlewood Treaty” was mentioned. Filler text was inserted in place of the earlier material, thus changing a dynamic article into something quite nondescript and reasonably sterile.

Most assuredly, the fact that Mr. Peters advocated using an altogether different English version of the treaty as the basis of our legislation, in place of the “official” English version, was immensely newsworthy. If the treaty interpretation we adhered to was, indeed, wrong it was the story of the century for New Zealanders.

Here are the two articles in larger print; one with the dynamic early edition text and the second edition, about an hour later, which had been hurriedly rewritten to strip out and censor any reference to the document found by the Littlewood family in 1989. It appears that journalist, Helen Tunnah, who co-wrote the highly revised second article, was acting in the capacity as an ideological officer doing damage control.

DIRTY TRICK NUMBER 2 … PSEUDO-HISTORIANS TRYING TO CAUSE CONFUSION BY CLAIMING THERE ARE MANY “VERSIONS” OF THE TREATY OF WAITANGI.

Our in-the-pocket, sold-out, main-stream historians, like Claudia Orange, attempted to “muddy the waters” in claiming that there are so many differing “versions” of the Treaty of Waitangi that we can never truly pin down what the true meaning and intent of the original text actually is.

This is a blatant lie, as it was a well-known fact that there’s only one Treaty of Waitangi and it’s in the Maori language. This fact is fully corroborated by long-standing international law, wherein a “treaty” has to be in the native language of the people with whom a treaty is being sought and secured.

THE PRE-EMINENT STATUS OF THE MAORI TEXT OF "TE TIRITI O WAITANGI"

There is only one Treaty of Waitangi.

Lieutenant Governor William Hobson recognised that there is only one legal Treaty of Waitangi text, and it is in the Maori language.

This singular recognition was affirmed by Hobson in his letter of instructions to Major Bunbury, wherein he wrote:

'The treaty, which forms the base of all my proceedings was signed at Waitangi, on the 6th February 1840, by 52 chiefs, 26 of whom were of the Confederation, and formed a majority of those who signed the Declaration of Independence. 'This instrument I consider to be de facto the treaty, and all signatures that are subsequently obtained are merely testimonials of adherence to the terms of the original document' (see: The Treaty of Waitangi, by T.L. Buick, pg. 162).

On the 17th of February 1840 the C.M.S. Mission press produced 200 printed copies of the Maori language treaty, as a paid consignment ordered by Hobson.

There was no production of an "official" English treaty text, as there wasn't one.

Subsequently, ALL of the large, handwritten copies of the Treaty of Waitangi, commissioned and produced by the government, then officially sent to the treaty signing assemblies around New Zealand, were in the Maori language and there were no departures from this strict practice*

*Appendix Note: Some will try to argue that the English language document that received signatures at Waikato Heads on 11/4/1840, as well as at Manukau on 26/4/1840 is an exception, but this is not the case. The only document ever officially issued by the government and intended to be used at Manukau and Waikato Heads now goes by the title of the Kawhia Treaty, which was in the Maori language. Because it did not arrive in time for his meeting, Reverend Robert Maunsell innovated and used a "printed Maori" text for presentation to the assembled chiefs and their tribes-people and allowed overflow signatures to spill onto a ruined Formal Royal Style English copy, produced solely for overseas despatch, which had come into his possession. Later, the Maori text sheet (with 5 signatures) was affixed atop the English sheet and the two unauthorised pieces of paper sent to Hobson as one, with the Maori language sheet representing the text presented and the large, scrap, English sheet merely a repository for overflow signatures.

The above-mentioned departure from the norm will be explained in detail as we proceed.

Treaty Consultant, Brian Easton, noted:

'For further evidence of the low status of the various English versions after the signing of the Tiriti, consider the numerous translations made in the 1840s by those involved in land deals around Auckland.... If everyone was translating the Tiriti, then they are implying the official version in English was non-existent, unimportant, or irrelevant.

‘In the 1840s the general view among settlers seems to have been there was no Treaty of Waitangi, but there was Te Tiriti o Waitangi which had to be translated into English....Ross reports on five versions which Hobson forwarded to his superiors in Sydney and London. There are differences between them’.

The main difference is that three have the Hobson-Busby preamble, two the Freeman one. One omits 'forests, fisheries'. A sixth version attributable to Hobson is in Clendon's letter to the Secretary of State on 7 July, where the preamble is again Freeman's (but 'forests, fisheries' are included)’.

What are we to make of all this? Surely it is that there was no English text of the Tiriti at the time of signing, or shortly after, that Hobson cobbled together what they could after recognizing the lack' (‘Was There a Treaty of Waitangi, and was it a Social Contract?’ Archifacts by Brian Easton, April 1997, p. 21-49).

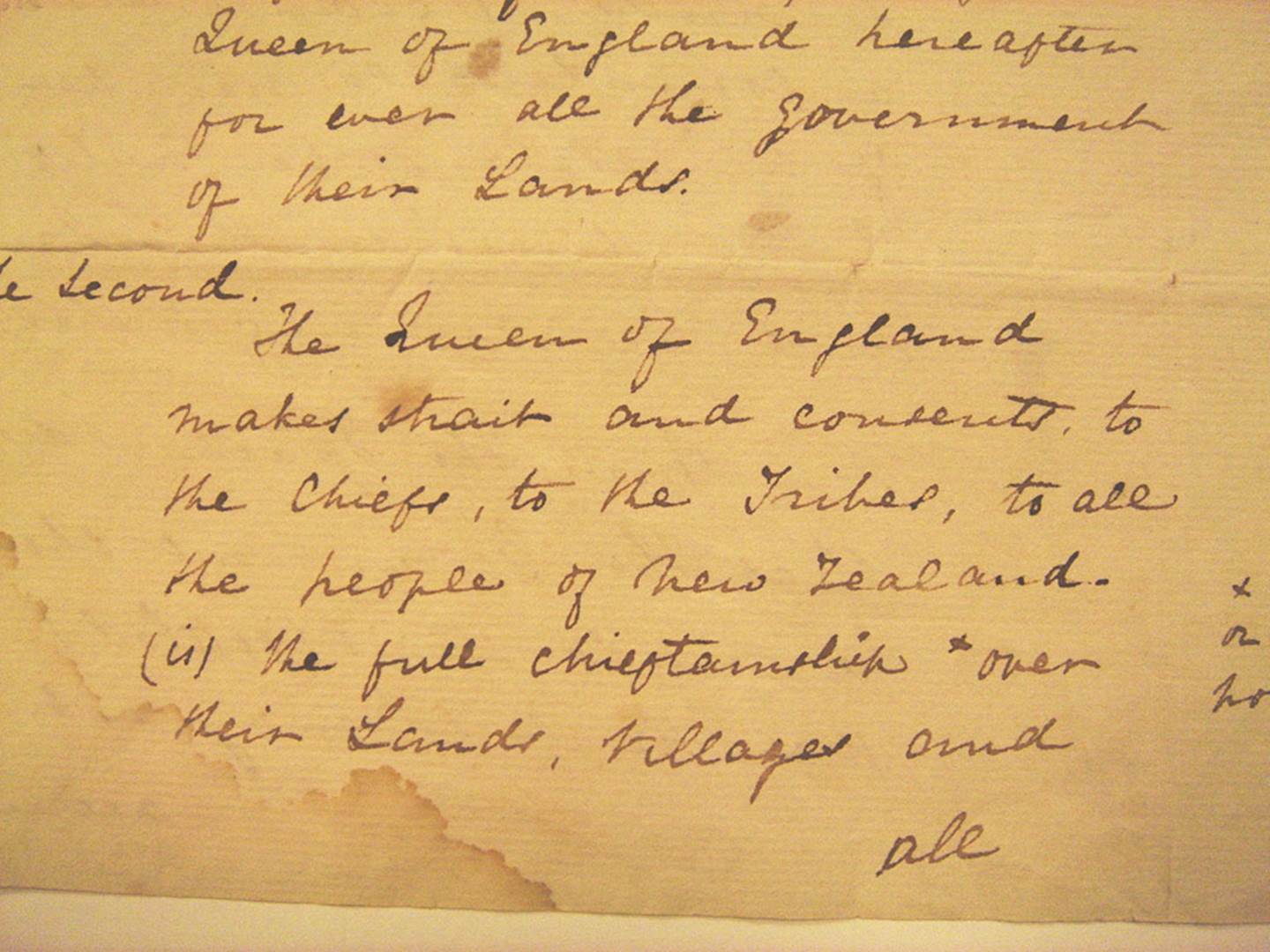

This is a back-translation of the Maori language Tiriti o Waitangi from the 1840s, found in the Clendon House Papers. The very innocent and benign Article II of the treaty, seen in back-translated form as in this example, has been so distorted in its new, modern interpretation, as to be a radical departure from the original intent.

THE MAORI TIRITI O WAITANGI GUARANTEES EQUAL RIGHTS FOR ALL NEW ZEALANDERS.

Article II states:

Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite kA wakaae ki nga Rangatira ki nga hapu-ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani - The Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the chiefs and the [families] tribes and to all the people of New Zealand -te tino rangatiratanga o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa. -the possession of their lands, dwellings and all their property.

In keeping with this unifying theme, as Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson shook hands with each signatory chief at Waitangi on the 6th of February 1840 he said, 'He iwi tahi tatou' -'We are now one people'.

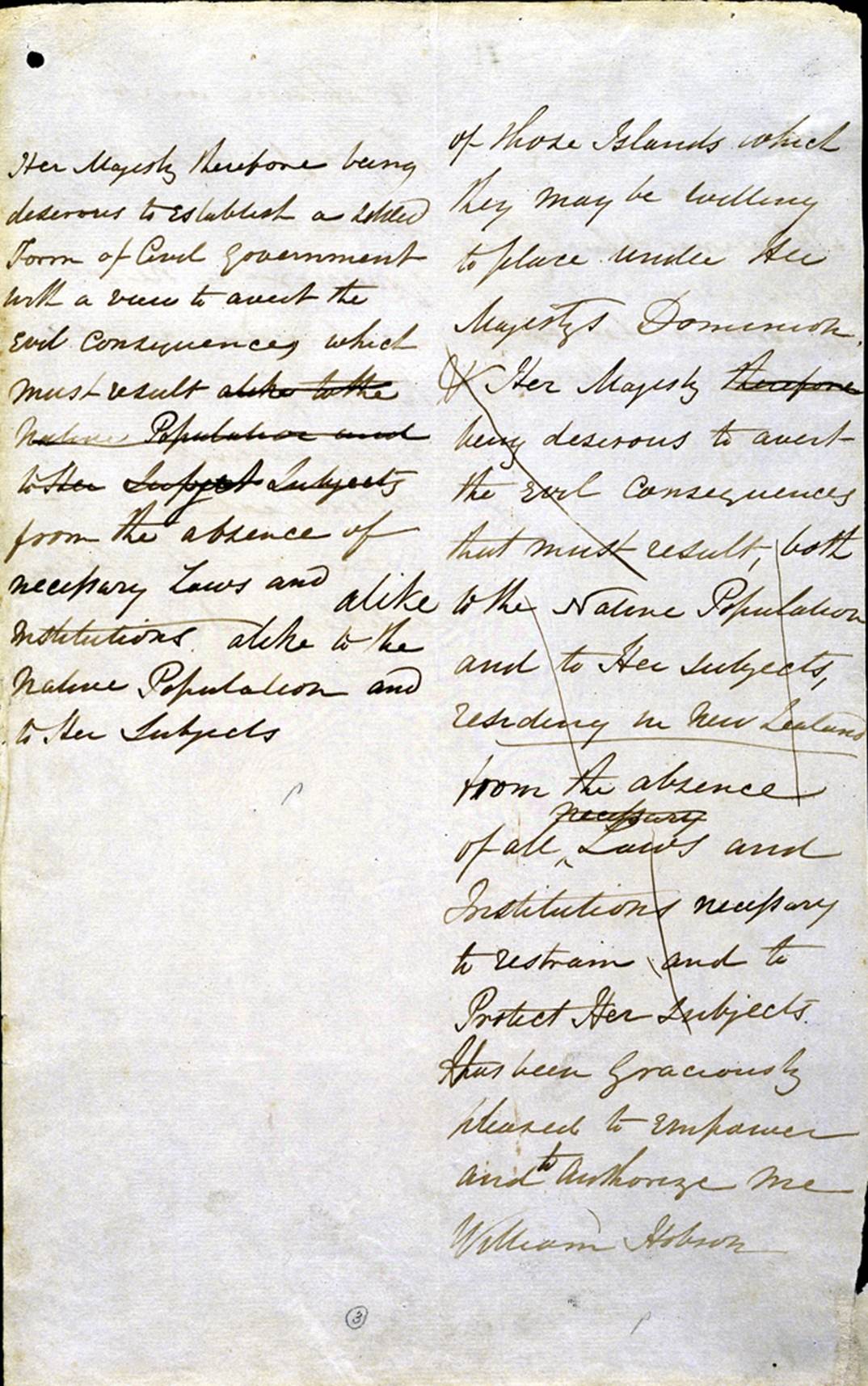

Even the obsolete early "rough draft" notes, written before the "final draft", affirm that Hobson's sole intent from the outset was to establish an all-encompassing, egalitarian society, wherein everyone was subject to the same laws & privileges, with no special rights set aside for any one group over another. In Hobson's handwriting we find:

‘Her Majesty therefore being desirous to establish a settled form of civil Government with the view to avert the evil consequences which must result alike to the native Population and to Her Subjects from the absence of necessary Laws and Institutions alike to the Native Population and to Her subjects…Has been graciously pleased to appoint and authorize me William Hobson…’ (see Facsimiles Of The Treaty Of Waitangi, with Lithographic originals first printed in 1877, Reproduced by A.R. Shearer, Government Printer, 1976).

The categories of English Treaty texts:

To the Most High and Mighty Prince James,

by the Grace of God,

King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland,

Defender of the Faith, &c.

The Translators of the Bible wish Grace, Mercy, and Peace,

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Great and manifold were the blessings, most dread Sovereign, which Almighty God, the Father of all mercies, bestowed upon us the people of England, when first he sent Your Majesty’s Royal Person to rule and reign over us. For whereas it was the expectation of many, who wished not well unto our Sion, that, upon the setting of that bright Occidental Star, Queen Elizabeth, of most happy memory, some thick and palpable clouds of darkness would so have overshadowed this land, that men should have been in doubt which way they were to walk, and that it should hardly be known who was to direct the unsettled State; the appearance of Your Majesty, as of the Sun in his strength, instantly dispelled those supposed and surmised mists, and gave unto all that were well affected exceeding cause of comfort; especially when we beheld the Government established in Your Highness and Your hopeful Seed, by an undoubted Title; and this also accompanied with peace and tranquillity at home and abroad....etc., etc.

ENTER HISTORIAN RUTH ROSS (1920 - 1982).

The Labour political Party of New Zealand had narrowly lost the election in 1969 but were able to gain power in the election of 25th of November 1972. Two prominent long-standing members of the Labour Party were Norman Kirk, who became Prime Minister and Matiu Rata who became Minister of Maori Affairs.

Matiu Rata had introduced a New Zealand Day Bill to Parliament in 1971, but this was not passed. With his political party holding the reins of power in late 1972, however, he introduced the Bill again as a precursor to his far more extensive Waitangi Tribunal Act 1975, which was passed and had a huge, detrimental effect over New Zealand society for the next 40-years plus.

One of Matiu Rata’s ambitions was to bring an English language version of the Treaty of Waitangi into our legislation, to sit alongside the Maori language treaty and be co-equal to it … a seemingly very strange thing for a Maori parliamentarian to want.

For line-by-line accuracy of what the Maori language text said, he should have advocated bringing in the 1869 back translation of Te Tiriti o Waitangi *that had been officially asked for by the New Zealand Government and supplied by the Native Department. However, Matiu Rata was ultimately able to introduce one of the Formal Royal Style composite versions and have it accepted as the Official English text of the Treaty of Waitangi.

*Note: The 1869, NZ Government commissioned, official back-translation mirrors the meaning and intent of Te Tiriti o Waitangi perfectly and in lieu of the actual (lost) Final English Draft, was the only legitimate English language text to place into legislation.

In an atmosphere of submissions to the government from the New Zealand Maori Council, calling for greater observance and honouring of the Treaty of Waitangi, etc., historian Ruth Ross wrote a scholarly article pointing out major discrepancies, contradictions and lost records in the treaty paper-trail from 1840. She, like so many others, had to conclude that, ‘Unfortunately the English text given to Williams does not appear to have survived’.

New Zealand historian, Ruth Ross, tried to make sense of the significance of the many Royal Style treaty composites and how or if they related to Te Tiriti o Waitangi Maori language text.

DIRTY TRICK NUMBER 3 … MODERN MAINSTREAM HISTORIANS TRY TO CONVINCE THE PUBLIC THAT TE TIRITI O WAITANGI WAS TRANSLATED FROM AN ENGLISH FORMAL ROYAL STYLE VERSION.

Despite admitting in one breath that the Final English Draft, “Unfortunately ... does not appear to have survived” or “has not been found”, our mainstream treaty historians still, deceptively, tell the public that Reverend Henry Williams’ translation was derived directly from the obsolete, rough draft notes penned between the 31st of January and 3rd of February 1840, whereas we know that the Final English Draft was written on the 4th of February 1840.

Let’s look at the totality of the 16-pages of pre-treaty rough draft notes to see if there is anything in there that could qualify as a complete “Final English Draft”, sufficient to hand to Reverend Henry Williams and his son Edward Marsh Williams for translation into the Maori language Tiriti o Waitangi.

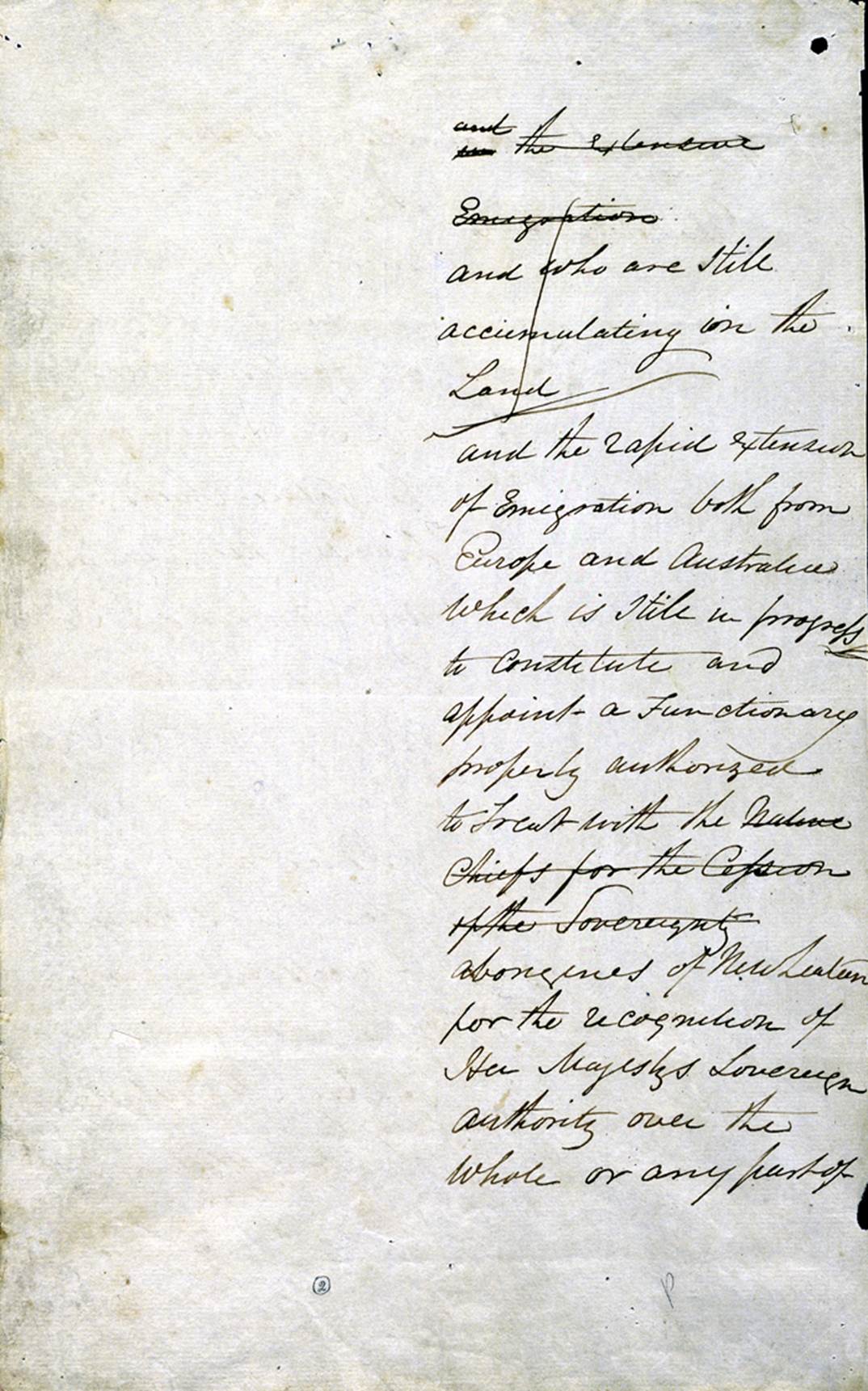

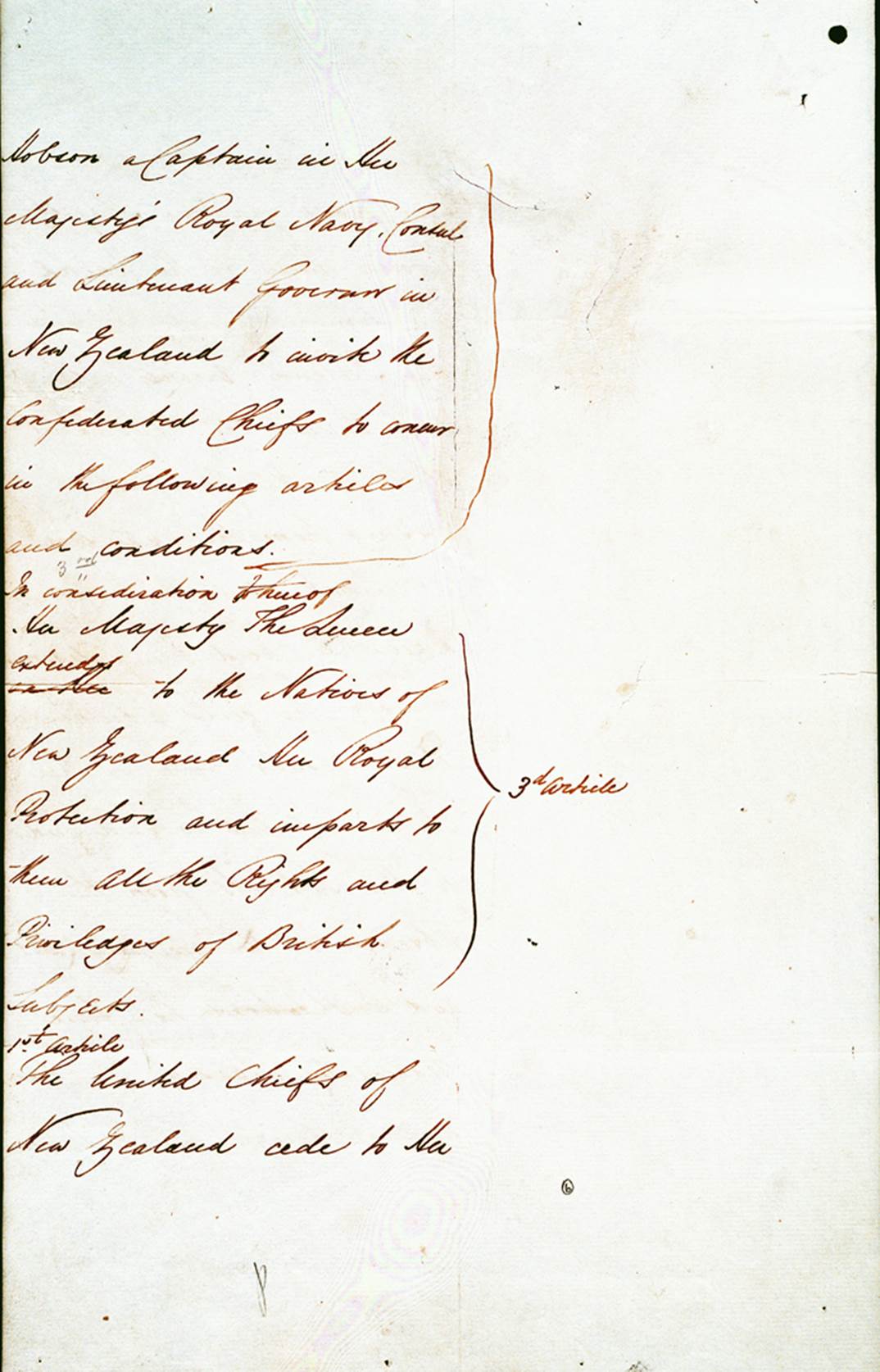

Captain William Hobson’s rudimentary ideas of what he would say in the preamble section of the Treaty of Waitangi. This page was written between the 31st of January and 1st of February 1840.

Hobson’s second page of rudimentary ideas related to what is to be said to the chiefs in the final draft. He’s still working on the preamble section, leaving space to the left for additions or text changes.

Hobson continues to labour over the wording of the preamble. Note the large sections of crossed out text to the right and possible, alternative, replacement wording to the left.

Hobson continues to struggle to write a coherent text. One major impediment was Captain Joseph Nias of the HMS Herald, who was very argumentative and resentful towards Hobson and his incentive. They had a severe argument on the night of Saturday 1st of February, which left Hobson, who was in poor health, suffering from a severe migraine headache and confined to his cot. Incapacitated, he delegated some writing to his secretary, James Stuart Freeman, who authored the next 4 pages of rough draft notes.

Whereas Hobson got to a point where he was about to introduce Articles for the treaty, James Stuart Freeman did a rewrite, putting in some alternative introductory text for the preamble.

Freeman gets a preamble pretty-much together and begins to introduce very rudimentary text for a couple of Articles.

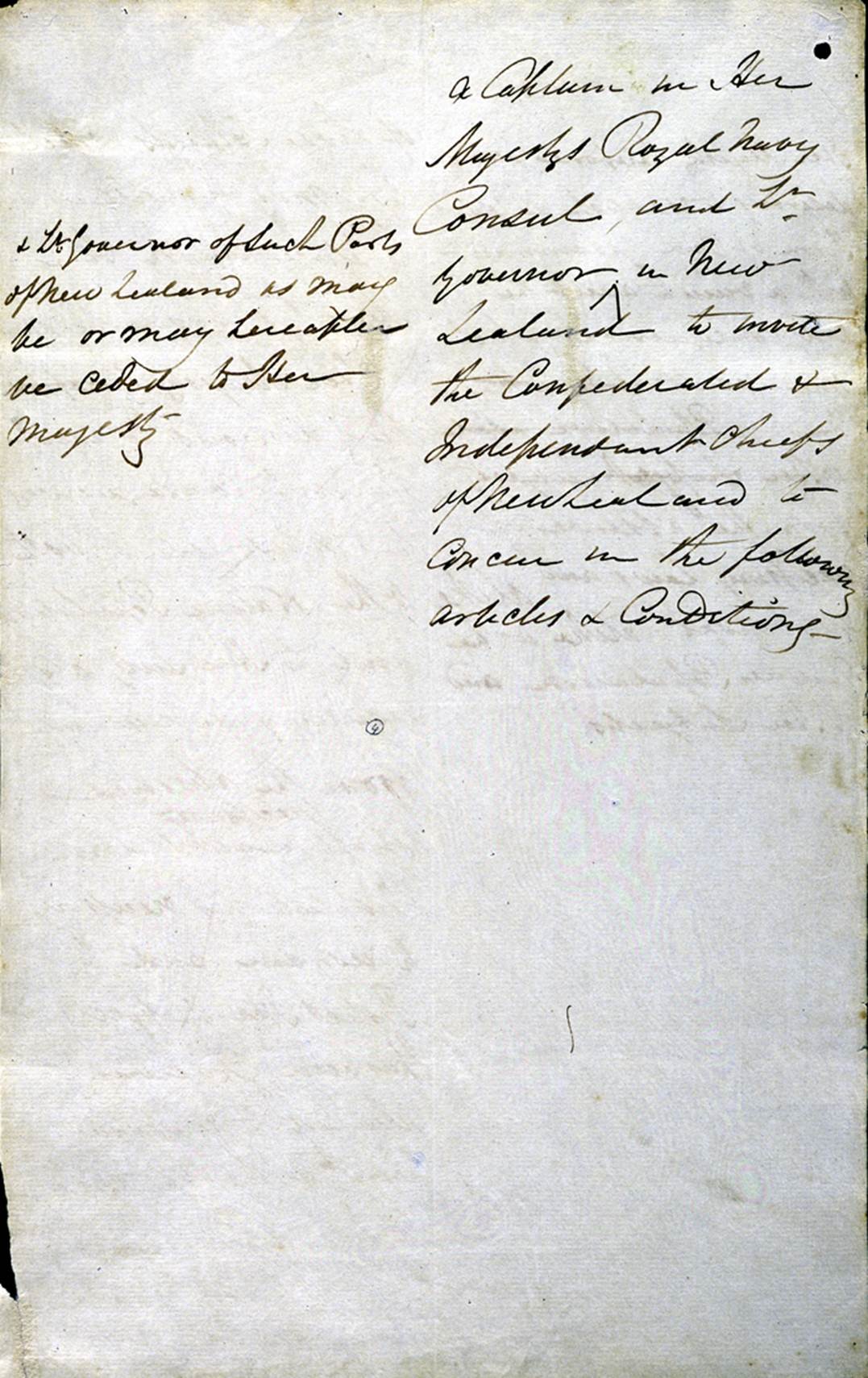

Freeman here pens a series of “latitude – longitude” references that never appeared in the later Treaty of Waitangi text. Clearly, with Hobson ill, the treaty drafting exercise was floundering, with the scheduled meeting before the chiefs only 4-days away.

This is as far as Freeman got and Hobson knew he needed a lot of help if he was going to be ready to meet the assembly of chiefs on the 5th of February and present them with a sound, eloquent proposition. Consigned to his cot aboard HMS Herald, he had no option but to call upon the expertise of James Busby, former British Consul who Hobson was replacing.

On the morning of Sunday 2nd of February 1840, he therefore had these scant, disorganised notes sent ashore to Busby, requesting his urgent help in fleshing out the main Articles of the Treaty and providing a final affirmation section, where the chiefs could agree to cede individual sovereignty to Queen Victoria and affix their marks or signatures accordingly.

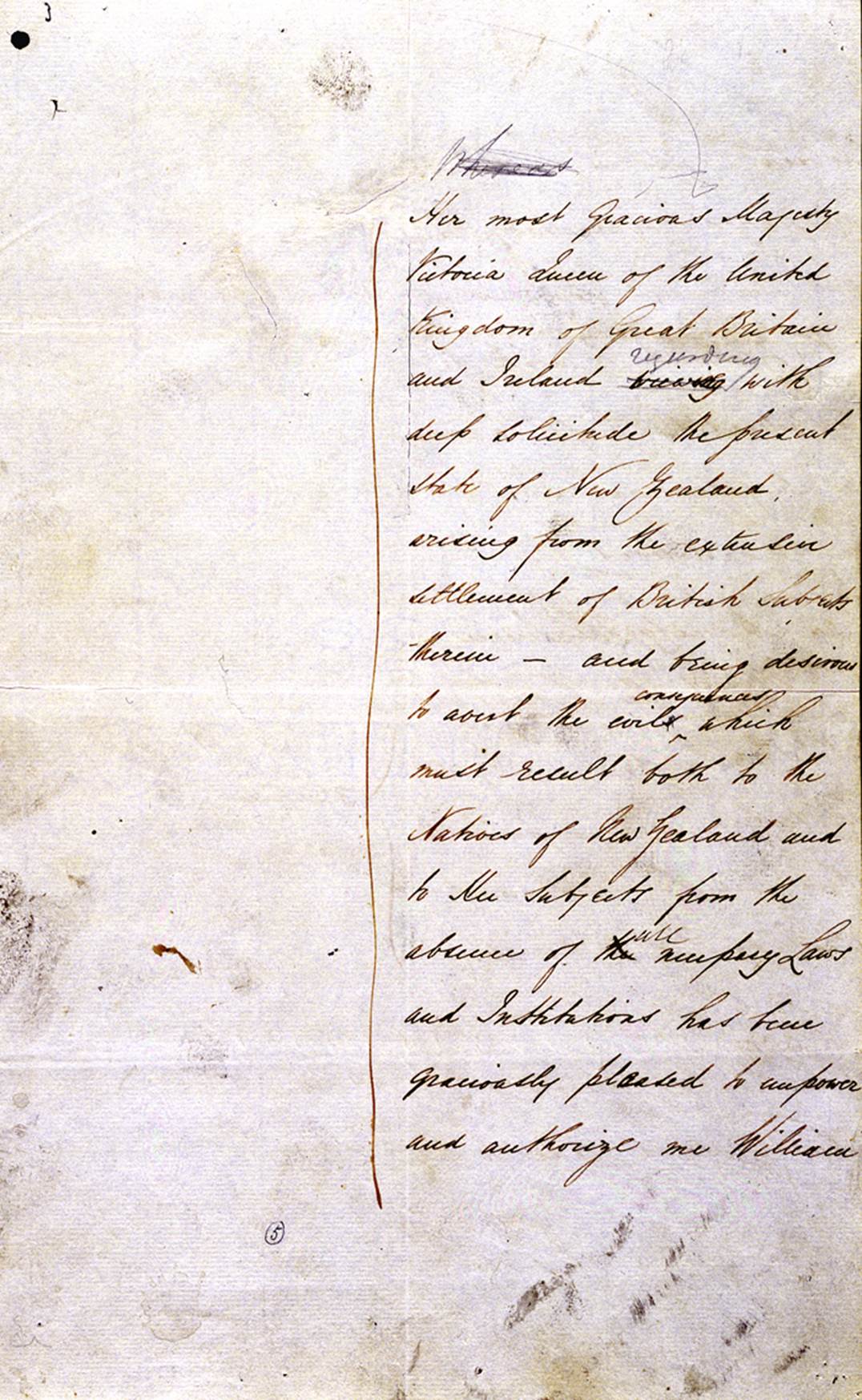

Busby, realising the urgency, immediately immersed himself in fleshing out the Articles for the treaty and put in a great deal of writing effort throughout Sunday 2nd of February 1840. He could see that Hobson had a reasonably adequate preamble, so didn’t attempt to rework that section. All that Busby wrote would ultimately have to be discussed with and agreed to by Hobson and a Final Draft written under Hobson’s direction.

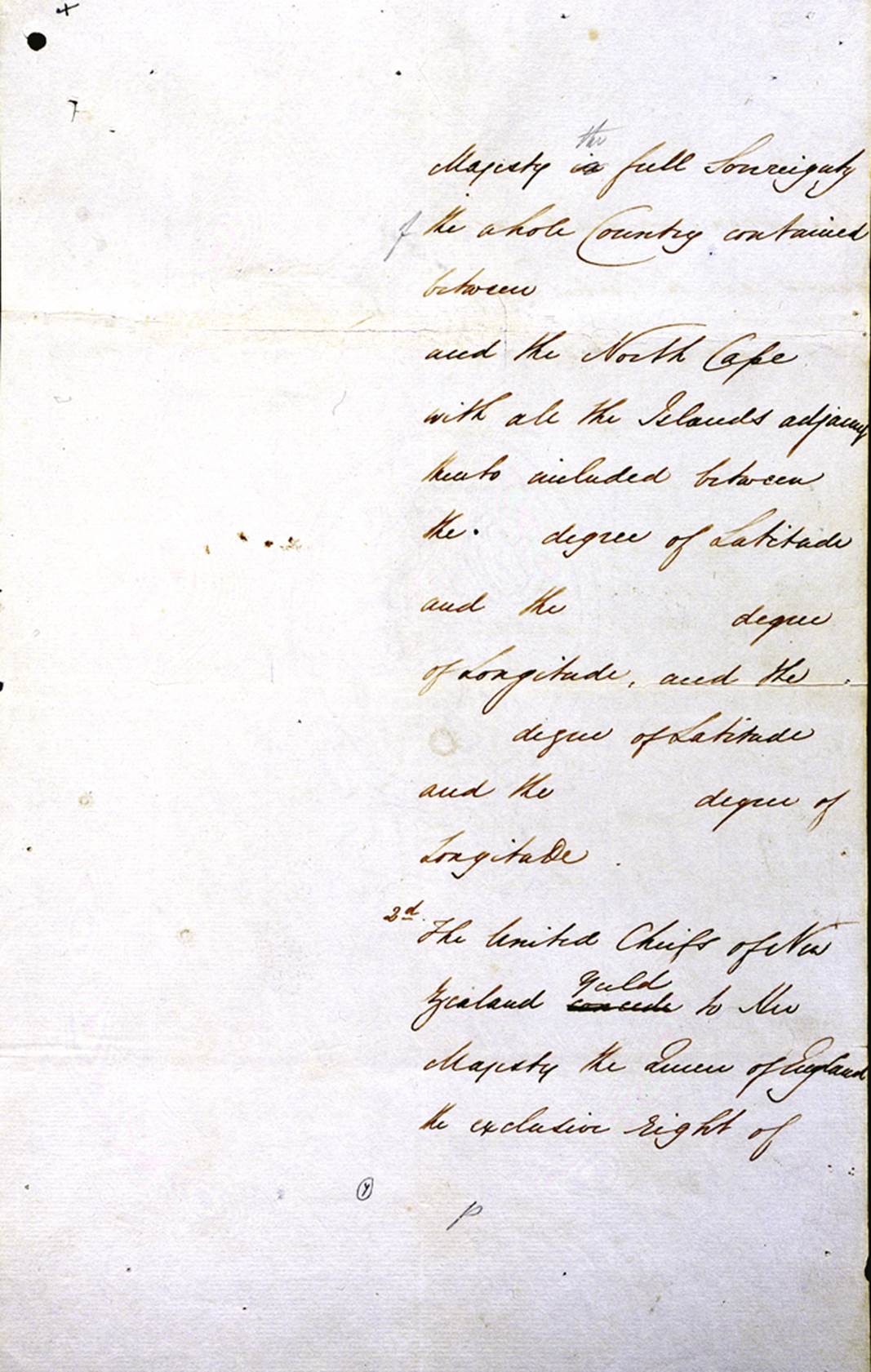

Busby continued to thrash out content for three Articles or proposals for the chiefs to consider only 3-days hence.

Busby, thinking Freeman’s references to latitude and longitude coordinates had some need for inclusion, added that text into his rough notes. However, in the Final Draft of the 4th of February, Hobson chose not to include any such reference.

Between Sunday the 2nd and Monday the 3rd of February, Busby completed his rough draft and would now write a cleaner copy to show Hobson later in the day, so that the Final Draft could be written and approved for translation into the Maori language.

It seems that reports coming to Busby on Sunday 2nd from Hobson’s staff concerning Hobson’s migraine headache condition, a direct consequence of arguments with stroppy, obstructive captain Nias, impelled Busby to get Hobson as far away from Nias as possible. He therefore arranged to meet Hobson for the final drafting session, not aboard HMS Herald, but ashore at Busby’s two room cottage at Kororareka in the late afternoon of Monday the 3rd of February 1840.

With Busby now at the helm of the treaty incentive, it was essential that he employ all available resources to take pressure off Hobson, such that Hobson could stand before the chiefs and present himself in full vigour as Queen Victoria’s duly appointed representative. Busby therefore marshalled his forces, including Reverend Henry Williams to oversee the translation and James Reddy Clendon to provide the comfortable, 8-room mansion venue for composing the Final English draft. During Monday 3rd of February Busby worked hard in writing up a “clean copy” of his treaty proposal for Hobson to scrutinise that evening.

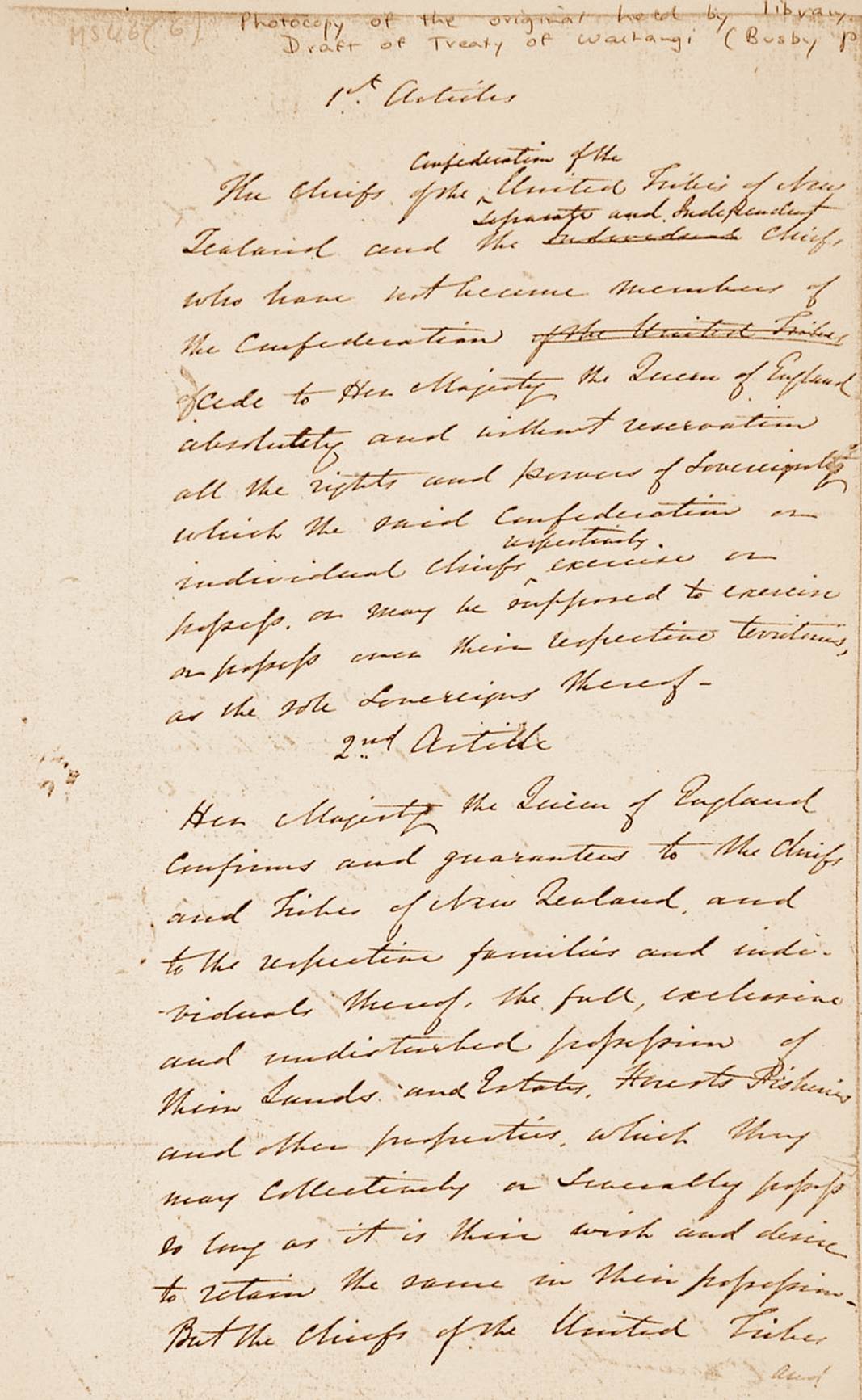

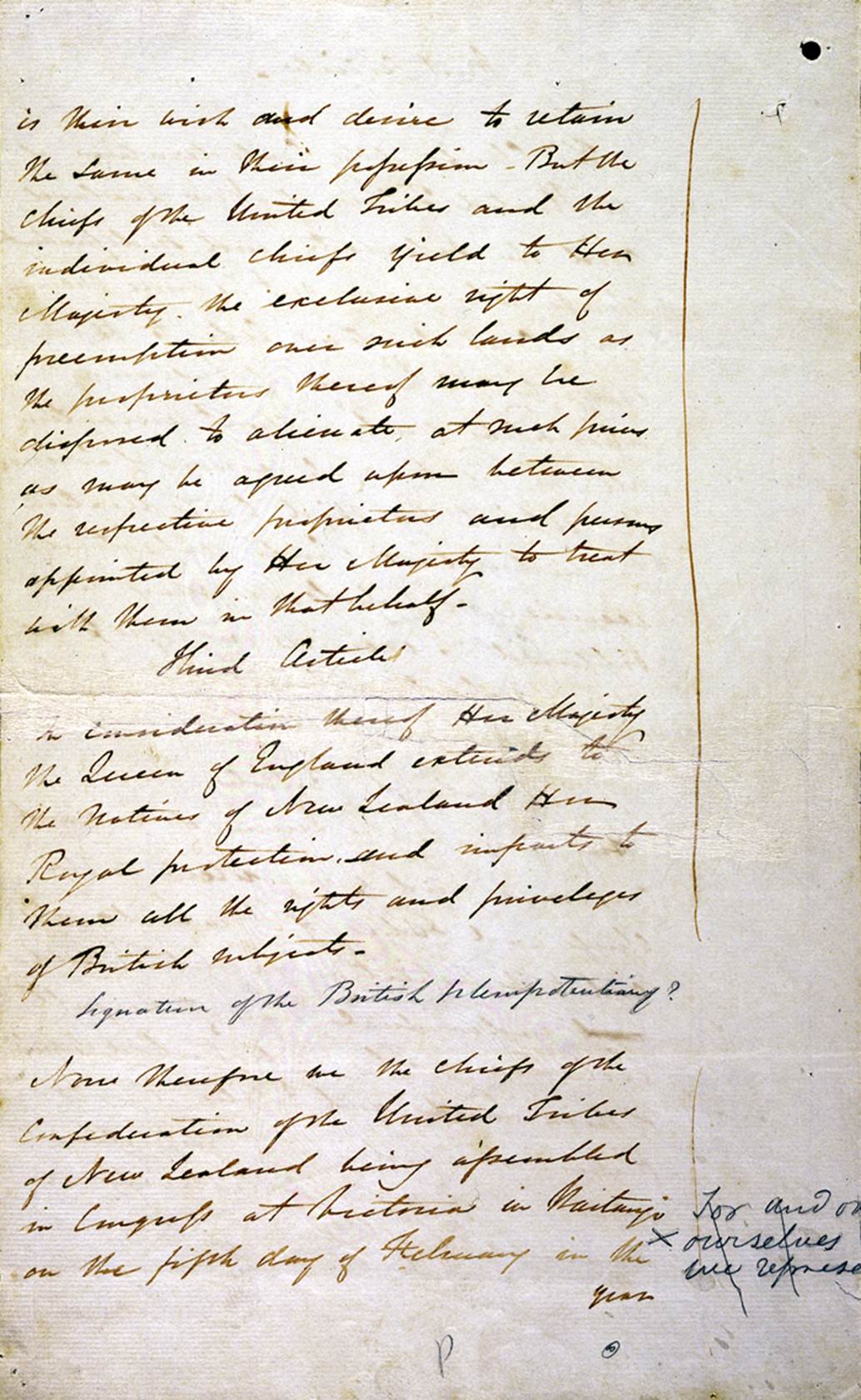

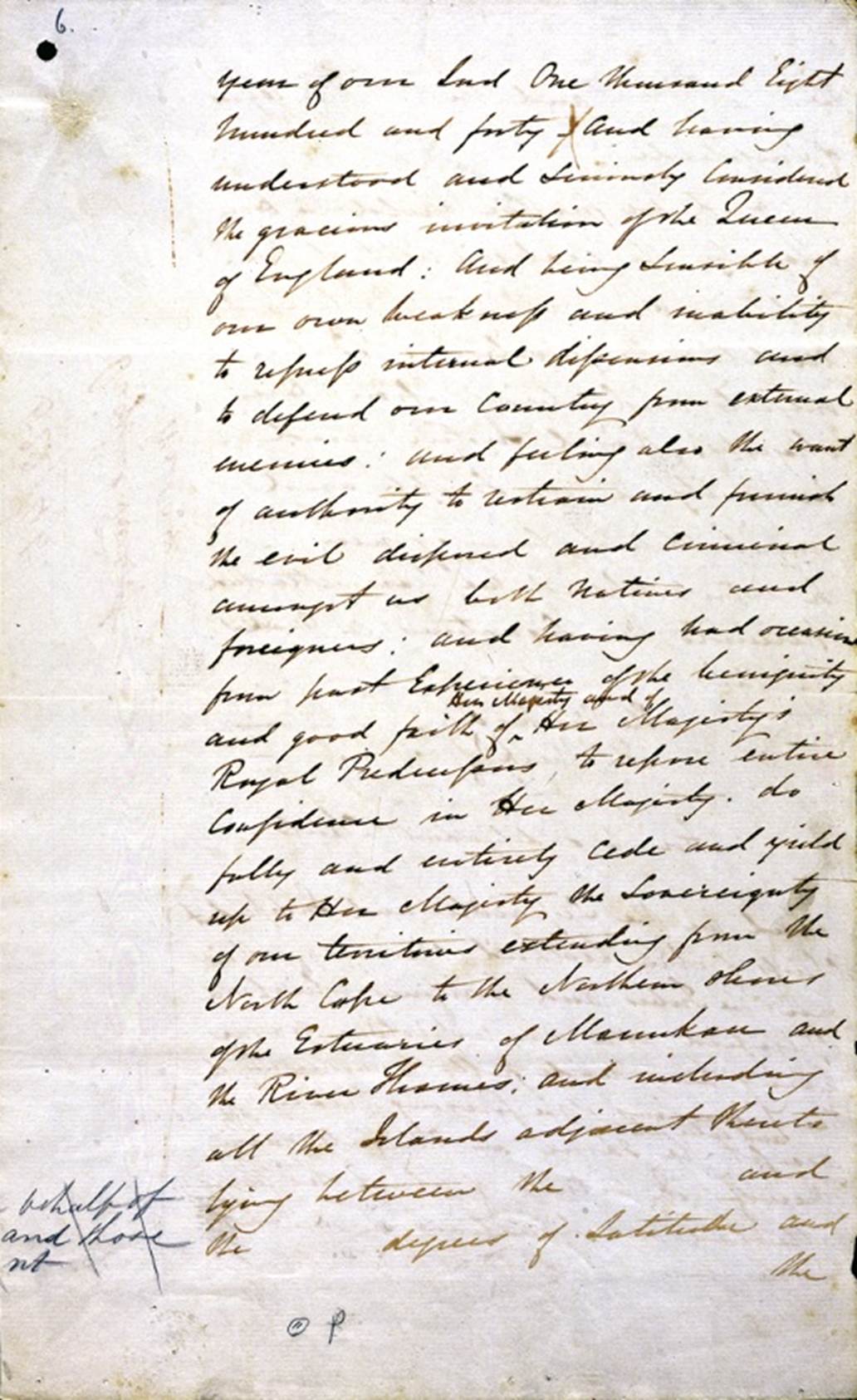

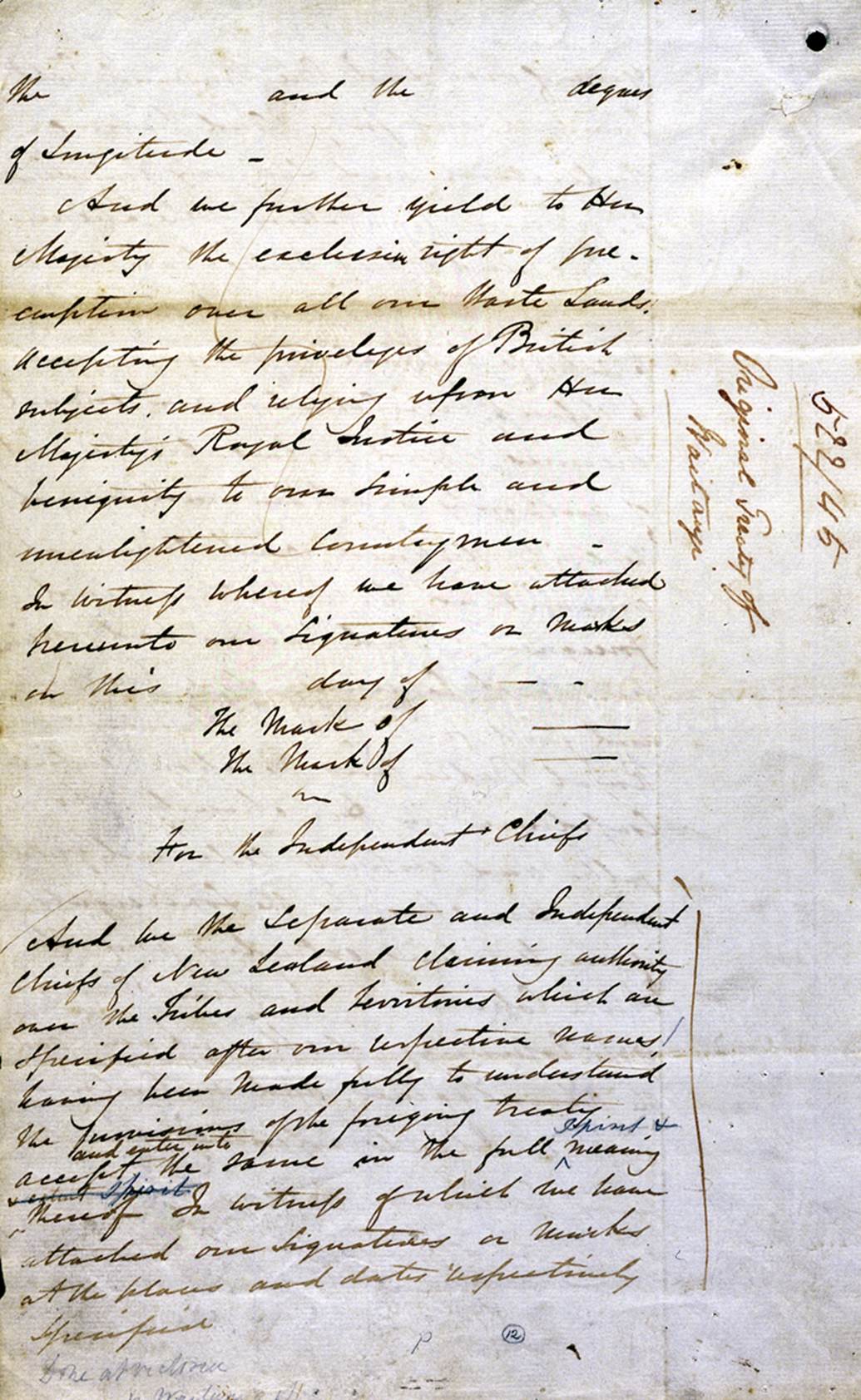

Page 1 of Busby’s “clean copy”, with the crossed-out text or spelling mistakes mostly eliminated, making it easier to decide on how the Final Draft should be worded.

Page 2 of Busby’s clean copy for Hobson’s consideration.

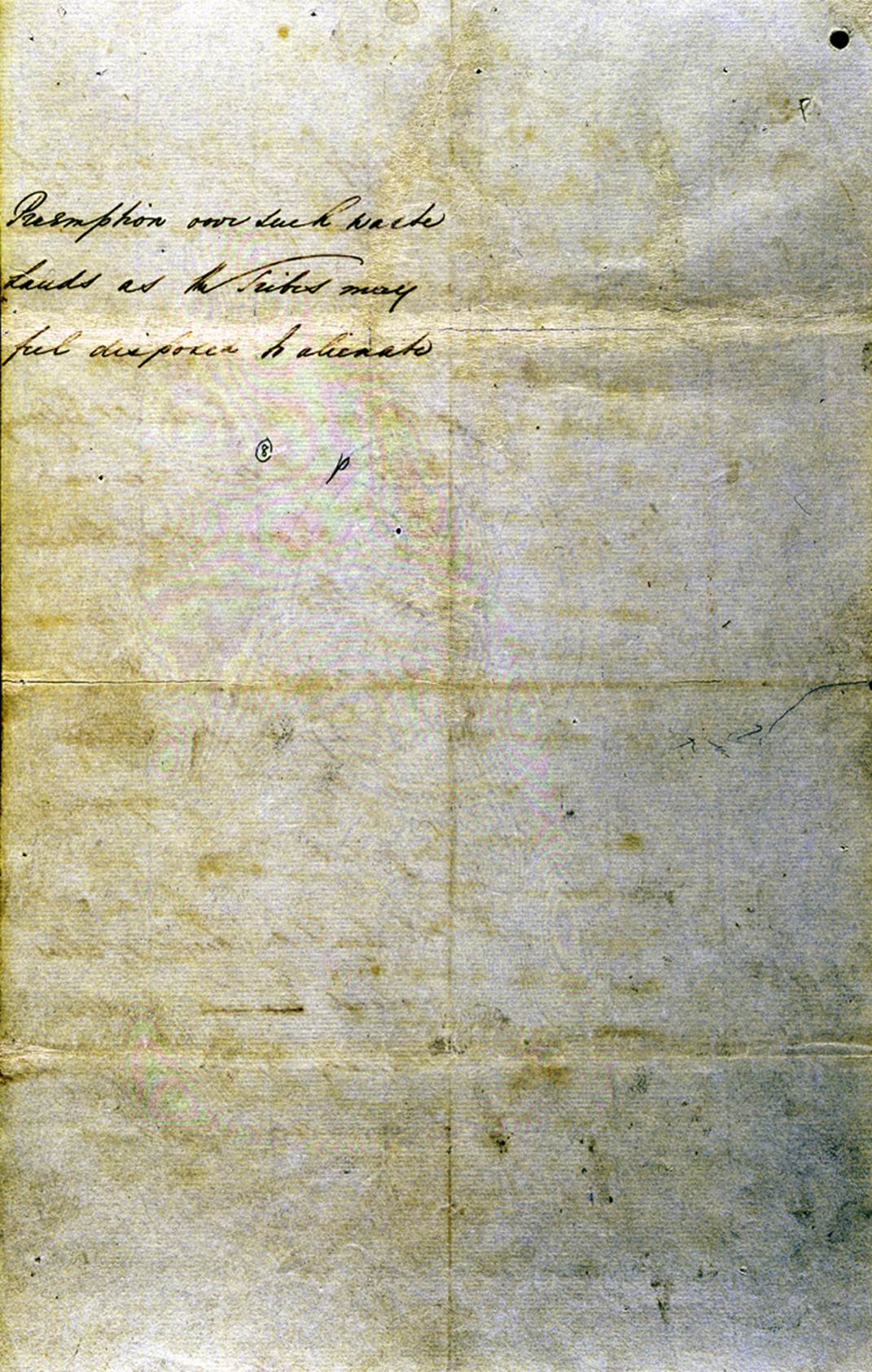

Page 3 of Busby’s “clean copy”.

Page 4 of Busby’s “clean copy”.

ALL OF THE FORGOING ROUGH DRAFT TREATY PAGES WERE WRITTEN BETWEEN THE 29TH OF JANUARY TO FEBRUARY 3RD AND WERE OBSOLETE WHEN THE FINAL DRAFT WAS WRITTEN ON THE 4TH.

By 1975 at least, a campaign was unleashed by longstanding Maori Member of Parliament within the Labour Party, Matiu Rata, as well as the Maori Council, that these very rough notes, or at least composite bits of them here & there, somehow contained the exact English Final Draft text that was used to create Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In and of itself, this hodgepodge jumble of crossed-out mistakes, additions, rambles and sometimes pretentious language that was virtually untranslatable into the Maori tongue (words like solicitude) was totally inadequate to hand over to translators to make any sense of.

WHAT DOES A TRANSLATOR NEED?

Hobson, Busby and any other advisors, constructing a treaty text, had an absolute obligation to provide a full and complete, clearly set-out document composed of words, sentences, paragraphs and concepts that the translators could easily understand. Obviously, there is nothing in the foregoing hodgepodge of confusion that could, by any stretch of the imagination, qualify as a finished English text to pass to a translator.

When historian, Ruth Ross, did her in-depth analysis in 1972, there was no English language draft text, known to her, that was capable of producing Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

As stated: ‘Ms. Ross noted that the English text used by Henry Williams as the starting-point for the creation of the Maori text “Unfortunately ... does not appear to have survived”, and Dr. Orange could only agree that no trace of “the final English draft” could be found’ (See: The Treaty of Waitangi, 1987 pp. 36-37).

(See also: Ruth M. Ross, Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Texts and Translations, New Zealand Journal of History 6#2, Oct. 1972, pp. 129-157, particularly pp. 132-136).

There is now, however, one document, discovered in 1989, that qualifies as the Final English Draft and here’s what it looks like:

This is the only known document, correctly dated the 4th of February 1840, that could qualify as the English Final Draft or mother document from which Te Tiriti o Waitangi was translated. Such a document must have a traceable pedigree back to Hobson, and this one has just such a pedigree … Littlewood family … back to 1840s – 50s solicitor Henry Littlewood … back to American Consul, James Reddy Clendon … back to Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson.

The Littlewood Treaty, which was Busby’s final draft of the 4th of February 1840 |

The Maori text translated by Reverend Henry Williams & Edward M. Williams 4-5/2/1840 |

Translation from the Original Maori by, Mr. T.E. Young, Native Department (1869) |

A translator will work line-by-line and sentence-by-sentence to render a translation that exactly duplicates the wording requirements of the original language script in need of translation.

Parts of speech within a translated sentence will often need to be placed in a different sequence, in order for the sentence to sound correct to the native speaker . All words or concepts mentioned in the original script will be translated, with no omissions, but no surplus words or sentences will be included if they did not appear in the original.

Line-by-line, the document found by the Littlewood family in 1989 perfectly duplicates the Maori text in meaning and word weight per sentence. It also duplicates the meaning of the 1869 back-translation commissioned by the NZ Government and supplied by the Native Department. The government needed an official back-translation due to interpretational problems arising out of the 1840s loss of the Final English Draft.