FROM AN ANCIENT SOLAR OBSERVATORY STRUCTURE, SOUTH HEAD, KAIPARA.

For capturing the summer solstice sunrise from an ancient New Zealand solar observatory, we had hoped to return to a dynamic site in South Taranaki and watch the sun emerge from the base of a "V" formed by the declining ends of two conjuncting mountains. However, because of draconian restrictions imposed on travel, due to the Covid19 hysteria, we were unable to venture any further southwards than the police blockade at Mercer, about 45-miles (72-kilometres) from home.

Our calculations in Red Shift astronomy program show, that from a giant hubstone at this South Taranaki site, the summer solstice sunrise "first glint" will be in the base of the "V" trough formed by the declining ends of the mountain in the foreground and majestic Mount Taranaki in the background. The day this photo was taken, unfortunately, the sky was like a patchwork quilt of chemtrails, crisscrossing the sky in all directions.

Being that we were in lock down and unable to venture south, we turned our attention to testing ancient solar observatory sites within the region where we could travel freely, without the imposition of having a swab crammed up our noses at some government designated border.

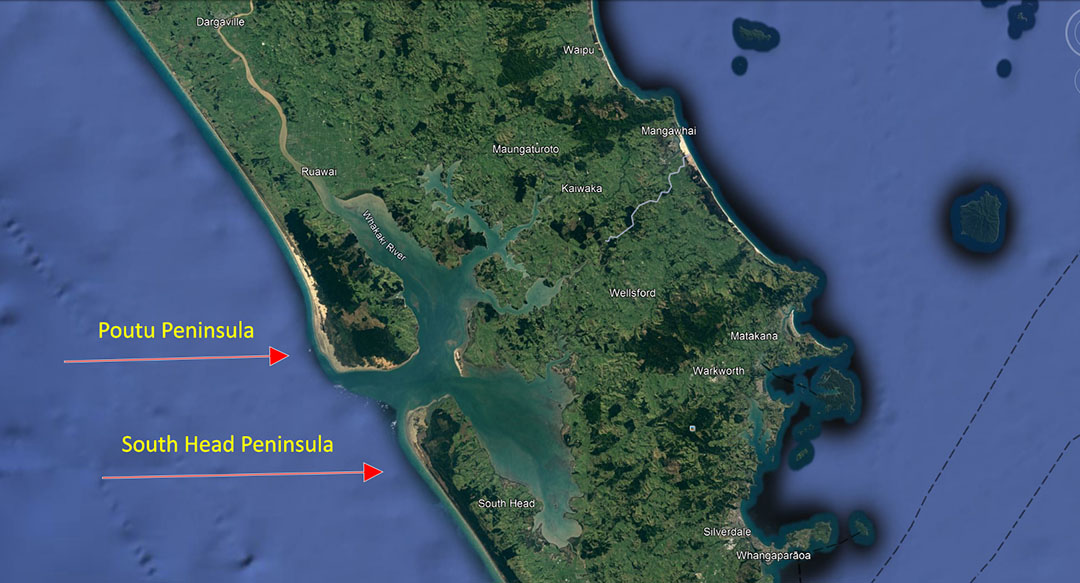

One major area of interest was a long, north-jutting peninsula bordering the huge Kaipara Harbour on the one side and the open sea on the other, where ancient habitation would have been idyllic ... a truly wonderful place to live, where seafood and other nourishing resources were, anciently, inexhaustible

The seaward side of the peninsula offers a wide beach highway that stretches for over 70-kilometres and the seashore, tidal sand is abundant in shellfish, which means that, even on the stormy days, when ocean fishing was not an option, shallow digging on the wet beach would be sufficient to provide plenty of food. Also, the sheltered inner harbour is home to a wide variety of fish and seabirds, whereas peninsula lakes and wetlands inland were abundant in eels, waterfowl, forest birds, etc.

Similarly, to the north of the Kaipara harbour entrance at South Head is yet another long peninsula, this time jutting southwards. This is the Poutu Peninsula which has a seacoast beach, extending from the North Head harbour entrance for over 100 kilometres to the Hokianga Harbour entrance.

Given that New Zealand is a sub-tropical country, in this northern clime the temperature between summer to winter fluctuates only about 20-degrees, meaning that in forested area windbreaks there were micro-climates that made the winter chills quite bearable and adaptable for people clad in light attire.

Throughout the vast sand dunes of the Poutu Peninsula there are many buried or semi-buried old ships that have foundered there and wrecked, some of ancient origin. According to the former curator of the Dargaville Maritime Museum, a ship dismasted in the Indian Ocean could drift seasonally on the monsoon currents and be dumped aground on the Poutu Peninsula. It seems drift mishaps occurred frequently during New Zealand's long history.

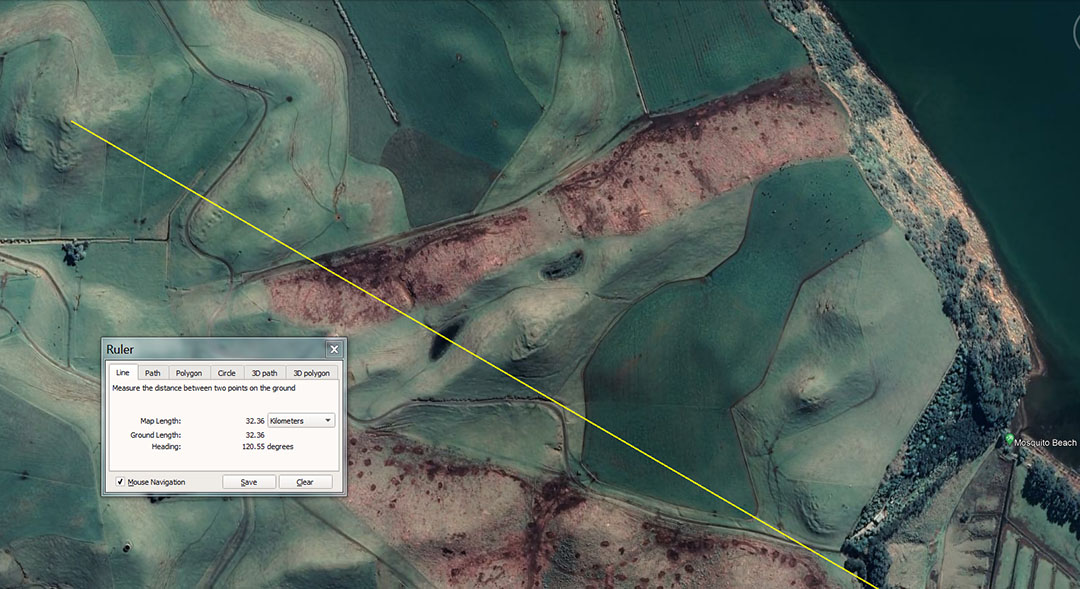

Our area of interest for getting a fix on the 2021 summer solstice sunrise was a batch of ancient carved hillocks near Mosquito Beach on the inner harbour side of South Head. Calculations using Red Shift astronomy program, Google Earth and some trigonometry concerning elevations of terrain indicated that first glint of the summer solstice would occur across the Kaipara Harbour from a prominent, historic elevated site at Wainui.

A series of anciently carved and terraced hillocks, also incorporating "sighting pits", sit on a close alignment that points towards the summer solstice sunrise position 32 kilometres away at a high elevation PA (fortress) region. The targeted outer marker bears the ancient names Te Rite a Kawe (Kawa) Rau ...or... Whero Whero. All of these South Head archaeological sites would give an accurate fix onto the distant summer solstice sunrise, with the much modified hillock at the centre of the picture resolving onto the highest point of the viewable horizon where "first glint" of the summer solstice sun is witnessed.

Recording the summer solstice rise position from the ancient solar observatory at South Head, with the site bathed in the morning glow of the sun. The centre summit has a sighting pit dug into it, with other pits and terrace viewing or surveying positions around the periphery. Many thanks to the farming family for permission to test the solar observatory attributes of these sites.

In close proximity to one of the much-modified hillocks was, what only can be described as an amphitheatre, a common type of structure found at sites where Patu-paiarehe or Turehu societies lived. At these assembly-areas the people would gather in for entertainment ... music, dance-displays, or speaking & singing very loudly. Of these ancient inhabitants gathered together in large cultivations, Reverend Richard Taylor (1855) wrote the following:

Besides gods the natives believed in the existence of other beings, who lived in communities, built pas, and were occupied with similar pursuits to those of men. These were called Patu-paiarehe. Their chief residences were on the tops of lofty hills, and they are said to have been the spiritual occupants of the country prior to Maori, and to retire as they advance. The Wanganui natives state, that when they first came to reside on the banks of the river, almost all the chief heights were occupied by the Patu-paiarehe, who gradually abandoned the river, and that even until a few generations ago, they had their favourite haunts there. These may be accounts of an aboriginal race mixed with fable; there are several things to warrant the idea that the Maori were not the first inhabitants of the land.

The Patu-paiarehe were only seen early in the morning, and are represented as being white, and clothed in white garments of the same form and texture of their own; in fact, they may be called the children of the mist. They are supposed to be of large size, and may be regarded as giants, although in some respects they resemble our fairies. They are seldom seen alone, but generally in large numbers; they are loud speakers and delight in playing the putorino (flute); they are said to nurse their children in their arms, the same as Europeans and not carry them in the Maori style, on the back or hip. Their faces are papatea, not tattooed, and in this respect also, they resemble Europeans. They hold long councils, and sing very loud; they often go and sit in cultivations, which are completely filled with them, so as to be frequently mistaken for a war party; but they never hurt the ground…

The belief in the Patu-paiarehe is very general; many have affirmed to me that they have repeatedly met with them. Albinos are said to be their offspring, and they are accused of frequently surprising women in the bush.’ (see Articles from “Te Ika A Maui, NZ and its Inhabitants”, by Rev Richard Taylor, written in 1855; facsimile reprint in 1974 A.H. & A.W. Reed).

From the carved hillock at site 2, South Head, a large, sweeping-curve amphitheatre structure is seen to the upper right. This would have been a wonderful, sheltered place for entertainment, oratory or counselling sessions. Wherever we find evidence of an ancient, sizeable population, we inevitably come across these areas that appear to have been modifications of the natural terrain ... to serve the function of an amphitheatre or place of assembly.

The summer solstice sun slightly obscured by horizon cloud, rising from the high terrain of Te Rite a Kawe (Kawa) Rau ancient settlement at Wainui, 32-kilometres distant. The local astronomer-priests of old, in residence at South Head, and very familiar with the distant horizon contours, could get a very accurate fix on the day of the summer solstice from this carved hillock at site 1, as well as two other closely aligned, nearby solar observatory sites.

Archaeological reports attest to the fact that South Head was once host to a very sizeable population. However, at the dawn of colonial civilisation it was found that very few Maori lived there, undoubtedly due to the years of carnage bourne out of inter-tribal fighting and "utu" (revenge killing) for historical slights, insults and grievances.

The earlier populations of Patu-paiarehe, Turehu and other inhabitants preceding the arrival of the Polynesian Maori warriors, had obviously lived here peacefully for generations, with no real animosities or threats from surrounding districts. This is very much in evidence within the artefact record of the area, with adzes, greenstone and other precious stones from very far-flung locations all over New Zealand. There are the high quality hard stone adzes from Tahanga Hill, Opito Bay, Coromandel Peninsula (144 kilometres away as the crow flies). Also, the precious green stone artefacts found here had to be acquired from rugged country streams, inland from Hokitika (750 kilometres distant as the crow flies). Then there was obsidian from far-away volcanic zones like Mayor Island (200 kilometres) and Taupo (300 kilometres), as well as chert-flint from either the far-away Wairarapa (450 kilometres) or further afield in the South Island, etc.

TE RITE A KAWA (KAWE) RAU... ALTERNATIVE NAME : TE WHERO WHERO.

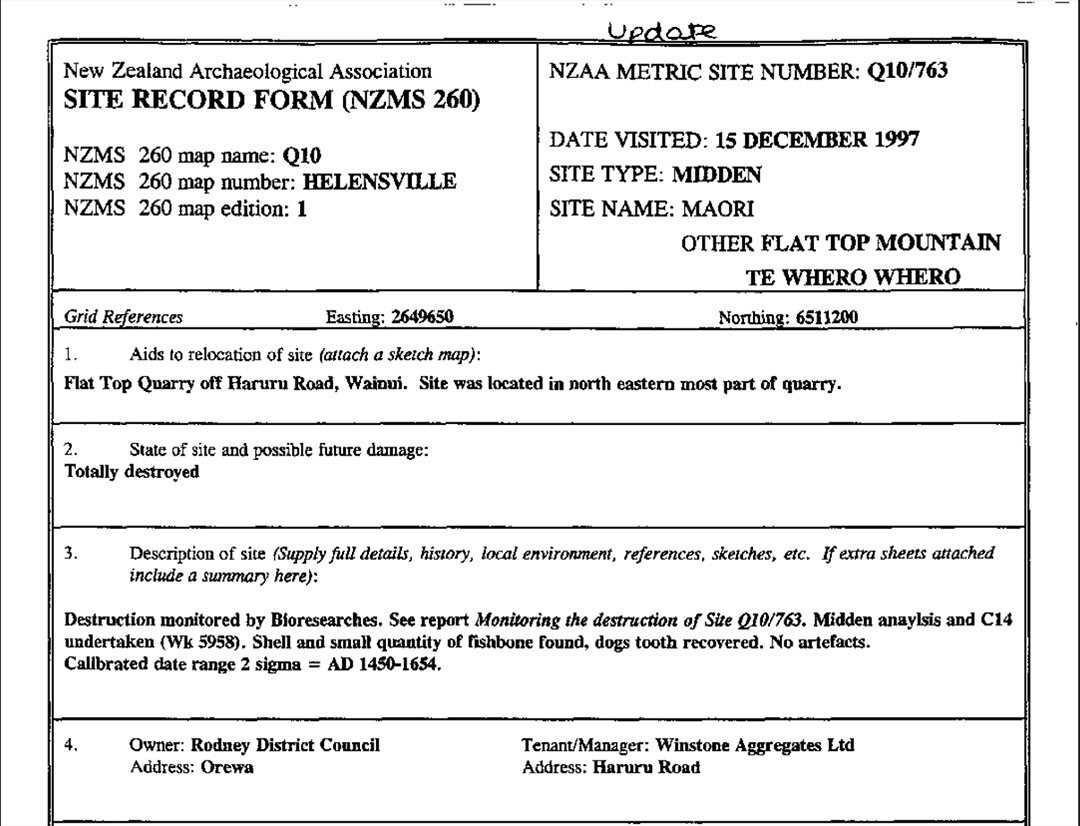

The region bearing the name Te Rite a Kawarau, also called Te Whero Whero encompassed this high hill composed of basaltic andesite of volcanic origin. Such a rich plug of solid, high quality stone is relatively rare, which led on to a quarrying enterprise by Highrock Quarries Ltd and Wainui Metal Transport Ltd in the 1940s. The quarry was purchased by Winstone Quarries in 1975 and, at this writing, the hill is reduced to mostly a hole in the ground. For many years it was called Flat Top PA or Hill, as it showed major signs of ancient occupation that extended well into the Maori epoch.

It's taken about 80-years so far, but the former high, andesite rock hill is all but gone and will have fully disappeared within a few years.

With the knowledge that this elevated region of the Kaipara Harbour's eastern hill range was the outer marker target for witnessing the summer solstice sunrise from a cluster of solar observatories at South Head, is it possible that the ancient name of the area contains clues related to the ritual passage of the sun?

We have in the Maori language:

Te: The respectful emphasis to a particular individual or thing.

Rite: comparison with.

A: by which.

Kawa: Formal activity, ceremony, prayers.

Rau: put into place, capture (as in a net).

In relation to a solar fix, the name could easily translate to: An auspicious ceremony to witness the placement or capture of (the sun) at a fixed position.

If the term Kawe (instead of Kawa) was used, then it means to carry, convey or bear. If used in reference to the sun's passage through the sky, Kawe, (in conjunction with Rau) could infer the sun being borne through the sky to land (be captured) at a fixed point.

SO, LET'S REVIEW SOME OFFICIAL MAORI ORAL HISTORY FOR THIS REGION:

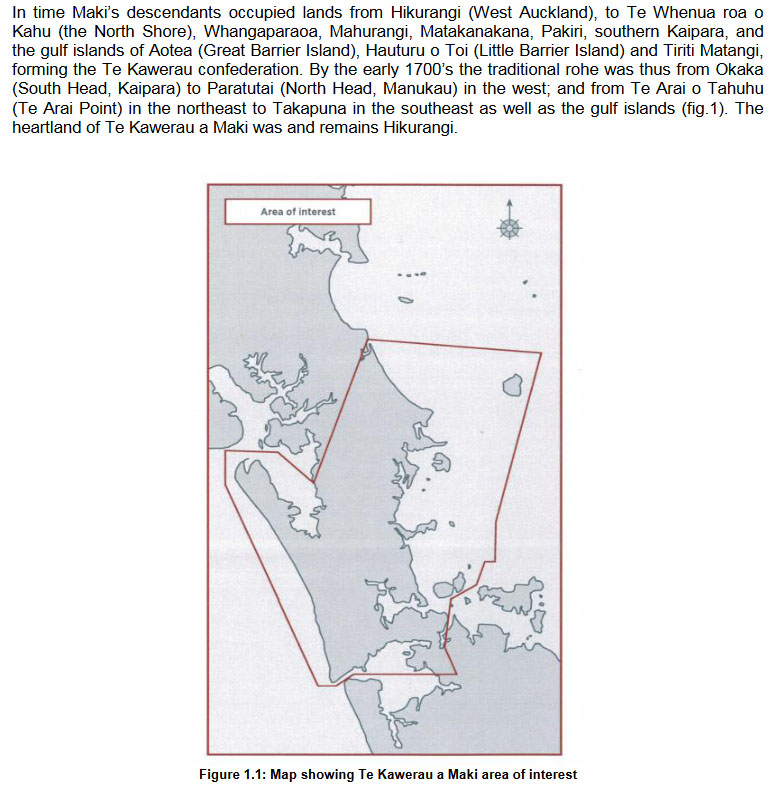

Earlier ancestors of the Ngati Whatua iwi (tribe) went by the name of Te Kawerau a Maki or the Kawerau people and groups within Ngati Whatua still identify with this more ancient name. It seems that in the normal toing and froing of inter-relating Maori groups, earlier iwi (tribes) or hapu (families) were absorbed by other more dominant groups and came under other umbrella terms. In the oral traditions of Te Kawerau a Maki we gain the following historical information:

'Te Kawerau a Maki were one of the earliest tribes to settle within the wider Auckland area. Our origins arise from the first inhabitants of the land - the Turehu, to the arrival of the Tainui, Aotea, Tokomaru, Kahuitara, and Kurahaupo canoes in the 14th century, and the Ngati Awa, Ngaoho, and Ngaiwi people who occupied the wider area prior to 1600.'

'Before humankind came to the islands of Aotearoa, they were inhabited by the Patupaiarehe, or as they are also known the Turehu or Nga Urukehu. These beings lived in the forests and wetlands and lived on their produce, avoiding cooked food entirely.'

'The Turehu – ‘those who arose from the land’ – were the first people in occupation of the Manukau area. In Kawerau tradition Tiriwa, a chiefly tohunga, is an especially significant Turehu tupuna of whom the Waitakere Forest is named after. Te Kawerau a Maki not only descend from the Turehu, but also from the many early tribal groups who migrated into the area.'

The term Nga Urukehu describes the Patupaiarehe or Turehu people, who occupied New Zealand for thousands of years before the circa 1300 AD arrival of the Polynesian Maori, as having a reddish, pinkish complexion. They were also described as having red, blond (also white or flaxen yellow ) hair ... ranging to brown & black, as well as blue or green eye hues ... ranging to brown, grey or black. Their physical anthropology (skeletal form, etc.) was quite different and distinctive from that of the Polynesian Maori.

As for the statement: These beings lived in the forests and wetlands and lived on their produce, avoiding cooked food entirely.' ... most certainly, for thousands of years the former, long-term inhabitants cooked Moa and many other species of birds or fish, kumara (sweet potato), etc., as evidenced by ancient middens locked in time capsules beneath tephra ash band layers from volcanic explosions of known date. However, in the dangerous era when the Patupaiarehe or Turehu were being hunted for cannibal consumption by the warriors, they avoided lighting cooking fires, as the smoke would give away their position. It was simply too dangerous to light fires, so food had to be eaten raw or be cooked, where possible, in the boiling water of volcanic pools (Rotorua or Taupo districts, etc.).

Another statement refers to an earlier people of the Auckland Isthmus who now go under the umbrella name of Ngati Whatua, These were the Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki tribe or sub tribe:

'Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki descend from the pre-fleet tangata whenua in Tāmaki, known as Patupaiarehe, and from early descendants of the Tainui waka. The eponymous ancestor of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki is Te Whatataao.'

Up until about 40-years ago, whenever the term tangata whenua was mentioned, it was well understood by all to refer to the much earlier inhabitants who occupied New Zealand for thousands of years before the circa 1300 AD arrival of the Polynesian Maori. Also, the Maori name used to identify these earlier people (Patupaiarehe) is anything but a term of endearment and means: The people you hunt and kill (with the blow of a club ... patu). Likewise, another name used by Maori as an identifier for Turehu tribes was Ngati Hua or "bastards".

To pretend these days that the Patupaiarehe and Turehu people (or all the other names and titles used by Maori across the length and breadth of New Zealand to identify them) were beloved ancestors is a bit of a stretch on credibility. These ancient people (also known as the Fairy-Folk) were forcibly hunted or bred-out into extinction, or as Rawene-based Tohunga, Hone Mohi Tawhai stated, ' they were absorbed in our race' (as either food or as slaves).

However, The Maori language is essentially Patupaiarehe, based largely upon the 10-generations that Maori lived 'under the mana of the Patupaiarehe', before 'war, strife, quarrelling were brought hither by the people of Toi'. The language has Indo-Aryan, Numidian-Libyan, Basque, Gaelic, Hebrew and Latin elements, etc., thus the word paiarehe probably contains an etymological root back to Fatum, Fata (Latin), Fae, Faere, (old French) or Peri, Parian, Pari (Persian Indo-Aryan)... all of which relate to the fairy-folk.

Of these people Maori historian, John Mitchell writes:

NGA TUREHU AND PATUPAIAREHE

'Nga Turehu are also depicted as a supernatural people and usually associated with elves and fairies (the fair-skinned Patupaiarehe). However, for a considerable period they inhabited the everyday world and for approximately ten generations coexisted in the South Island with the Polynesian descendants of Maui - i.e. the true Maori from Hawaiki). Eventually Nga Turehu, described as being a fair people with red or blond hair, were displaced into the hinterlands. In Te Tau Ihu they were believed to have occupied the hilltops and bush fastnesses in the Marlborough Sounds and Pelorus Valley until a comparatively recent date when they were smoked out by bush fires. The Turehu and Patupaiarehe were excellent netmakers and clothweavers and it is from these people that Maori acquired the same skills. The Turehu kidnapped Maori women as wives, some of whom managed to escape back to their own people, bringing netmaking and weaving skills with them. With their escape from the physical world Nga Turehu also became ephemeral beings; they were seen only in misty weather, and would vanish without trace if surprised.' * (See: Te Tau Ihu Te Waka, Pg. 44).

*Mitchell's final statement here describes Patupaiarehe and Turehu under siege and being relentlessly hunted by the Maori warriors ... flushing them out with bush fires, etc. They mostly had to hide by day and forage by night or in misty weather in order that their presence go undetected. In areas of New Zealand like Port Waikato they succumbed to lung ailments due to their lack of sunlight and the necessity of hiding by day in dark, damp caves.

TE WHEROWHERO ... THE SECOND NAME FOR TE RITE A KAWARAU.

'In 1825 a large Nga Puhi force armed with muskets invaded Tamaki Makaurau, defeating the various iwi and hapu and forcing the majority of the survivors to seek refuge in the Waikato. Despite their conquests, Nga Puhi did not follow up these victories with occupation as their invasion was a taua against those who were perceived to have wronged them. It was not until 1836, after a decade in exile, that Te Kawerau a Maki and the other iwi of the district were escorted back to Tamaki under the protection of the Tainui ariki Potatau Te Wherowhero.'

'There is no doubt that the Waikato tribes were a formidable force in 1840 and that their paramount leader Te Wherowhero had played a critical role in ensuring the various tribes were able to return to Tāmaki and the Manukau area after 1835. Both Tainui and the Crown were very useful allies for Ngāti Whātua to have in 1840.'

See: https://ngatiwhatuaorakei.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Ngati-Whatua-Orakei-closing-submissions.pdf

Indeed, the paramount Chief of Tainui was largely responsible for saving the lives of Ngati Whatua related tribes after the were attacked and defeated by Nga Puhi from the Bay of Islands and Hokianga of the far North of New Zealand. Te Wherowhero offered his protection for over a decade and, finally escorted the Ngati Whatua related survivors back to lands formerly occupied by them prior to the Nga Puhi invasion. It is probably in homage to this gesture by Potatau Te Wherowhero that Flat top PA, Wainui, once back into Ngati Whatua possession, was accorded the name of protector, Te Wherowhero.

Like so many others, Te Wherowhero is said to have claimed Patupaiarehe or Turehu lineages, as did Nga Puhi conquerors,Tamati Waka Néné and his brother Patuone.

The name Te Wherowhero means "Red red" and seems to be in deference to the Patupaiarehe ancestors.

After 1845, Nga Puhi Chief Eruera Patuone moved to Lake Pupuke, Auckland to offer protection to the fledgling New Zealand colonial government and Ngati Whatua showed him great respect ... lest disrespect lead to another disastrous confrontation with Nga Puhi.

The NZ Archaeological Association lists the second name of Te Rite a Kawarau as Te Wherowhero.

The high point of Te Rite a Kawarau, from which South Head observers could witness the summer solstice sunrise, also functioned as a winter solstice sunset observation post for ancient Turehu observers stationed at the designated sighting pit, mound or standing stone solar marker erected at Te Rite a Kawarau.

At the time of the winter solstice they would see the sun set into the trough of sea at the Kaipara Harbour entrance. They would also get a fix on the summer solstice sunrise as "first glint" occurred on the high central terrain of Motutapu Island in the Hauraki Gulf. The winter solstice sunrise would be atop the high centre of Great Barrier Island in the Hauraki Gulf.

By these observations on the significant, milestone solar days, occuring 4-times a year, calendars could be kept 100% accurate and all planting & harvesting could be done on time ... thus assuring the greatest chance of abundant crops and survival.

For some reason that has nothing to do with established, long-term history, the Ngati Whatua authorities have implemented a name change for the area, now to be known as Te rite a Kawharu (in homage to their recently deceased elder (2006), Hugh Kawharu?).

Martin Doutre, February 9th, 2020.