Further down by the lakeside on Otuparae Peninsula are the signs of ancient habitation, including this and several other pits. Some of these seem to have acted as sighting or observation pits for solar events, although at a much later, more hostile epoch, they undoubtedly became sentinel positions from which to detect approaching enemies.

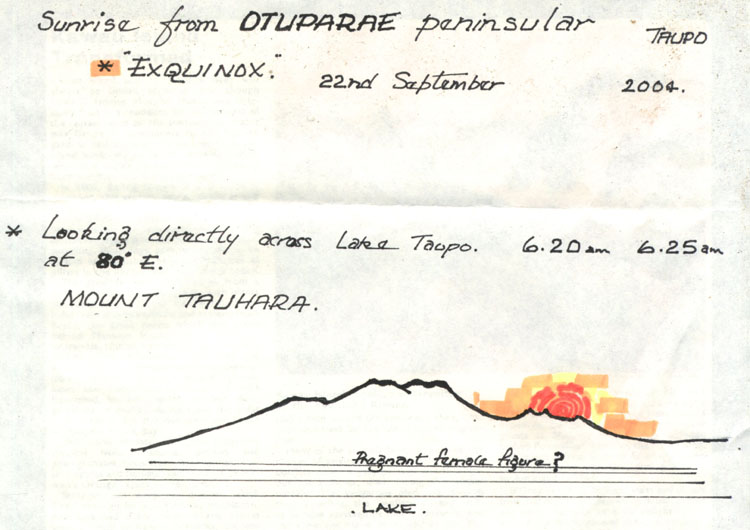

At the vernal equinox for the southern hemisphere, 2004, Taupo archaeological researcher Graham Parminter made this observation regarding the sunrise, which pretty-much duplicates the scene from the Tuhingamata Hill solar rise observatory.

From one of the sighting pits the target appears to be Maunganamu Hill, which acted as the equinoctial sunrise outer marker for a very important solar observatory situated across the lake on the eastern side.

Around Otuparae Peninsular are very ancient stone walls, some of which are bush covered and in a dilapidated condition due to root pressure and long abandonment. They are stacked-stone drywall.

There are also many former dwelling caves around the shoreline, this one at Otuparae Peninsula. At later epochs some of these became burial caves when the original inhabitants of the district were vanquished by the late arriving Maori warriors.

Another former cave dwelling and rock shelter.

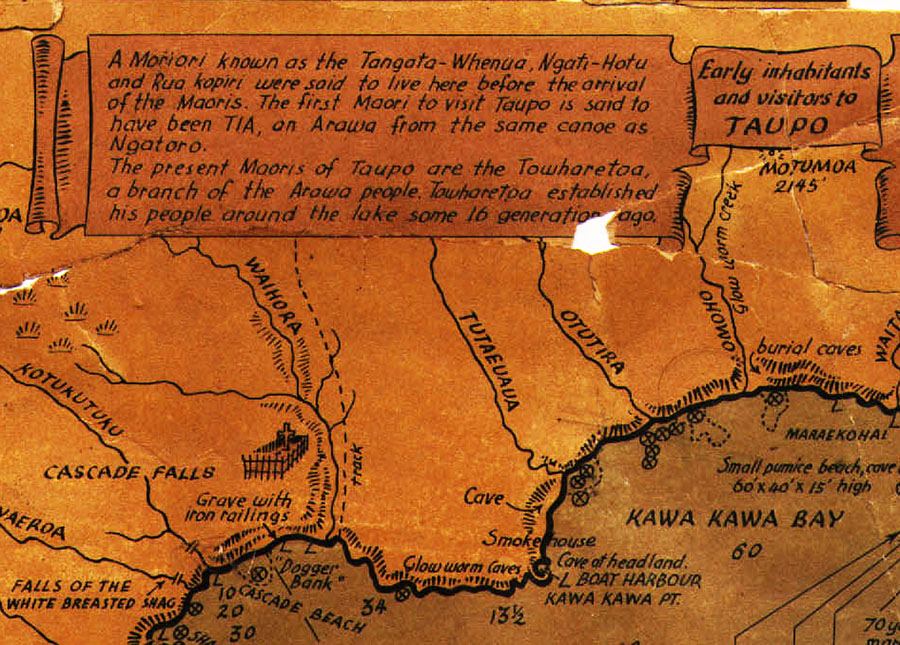

A 1920s tourist map of Lake Taupo provides snippets of, what these days would be, censored history that goes unmentioned in the cultural-Marxist versions taught in our schools. It makes mentioned of the once well-known fact that there was a long-established civilisation living in New Zealand before Maori arrived from Polynesia-Melanesia in about 1250 AD. The original inhabitants of the Taupo region were called, by Maori, Ngati-Hotu.

Here’s a description of what these people looked like:

‘Generally speaking, Ngati Hotu were of medium height and of light colouring. In the majority of cases they had reddish hair. They were referred to as urukehu. It is said that during the early stages of their occupation of Taupo they did not practice tattooing as later generations did, and were spoken of as te whanau a rangi [the children of heaven] because of their fair skin.

There were two distinct types. One had a kiri wherowhero or reddish skin, a round face, small eyes and thick protruding eyebrows. The other was fair-skinned, much smaller in stature, with larger and very handsome features. The latter were the true urukehu and te whanau a rangi. In some cases not only did they have reddish hair, but also light coloured eyes.’

(See Tuwharetoa, chapter 7, page 115, by Rev. John Grace).

Fairly close by at Lake Rotorua the original inhabitants there were described in similar terms:

An old Maori elder said the following to historian James Cowan about the former, vanquished Ngati-Hotu of Mt. Ngongotaha in Rotorua district:

‘The complexion of most of them was kiri puwhero and their hair had the reddish or golden tinge we call uru-kehu. Some had black eyes, some blue like Europeans. Some of their women were very beautiful, very fair of complexion, with shining fair hair…'

Here’s an account of their final demise:

The battle of the five forts

‘Ngāti Hotu were found living around the shores of lakes Taupo and Rotoaira by the Ngāti Tūwharetoa iwi (tribe) in perhaps the 15th century. Ngāti Tūwharetoa were then resident at Kawerau and associated with Te Arawa iwi which today occupies the area from the Bay of Plenty coastline to the Lake Taupo district. Ngāti Hotu suffered a major defeat at the battle of Pukekaikiore ('hill of the meal of rats')* to the southwest of Lake Taupo where Ngāti Tūwharetoa devastated them, causing the few survivors to flee.

Apparently some of the survivors settled around the village of Kakahi ('freshwater mussels') which lies 30 kilometres west of Lake Taupo. They were discovered there by a party of Whanganui Māori journeying up the river of the same name who soon called up reinforcements to attack the settlement. The Ngāti Hotu set up a ring of five forts around Kakahi which the Whanganui Māori attacked and took one by one until finally the last two, Otutaarua and Arikipakewa, fell. The final, brutal episode of the battle was played out on the flats between Kakahi and the Whanganui river when the now, effectively victorious Whanganui Māori hung the legs of fallen Ngāti Hotu warriors from poles mounted in the forks of trees - a gesture at which their remaining enemies broke and fled off into the depths of the King Country to vanish from history.

The battle is estimated to have occurred circa 1450 and its story has since been handed down through 15 generations to the Whanganui kaumatua Takiwa Tauarua, who related it to prominent New Zealand artist Peter Mc Intyre in the 1960s.’

*Footnote: The “hill of the meal of rats” refers to the fact that the defeated Ngati Hotu were cannibalised.

See: McIntyre, Peter (1972). Kakahi, New Zealand. Reed, ISBN978-0589007423

Similar descriptions as to the physical appearance of the original New Zealanders are found in the oral-traditions of Maori tribes across the length and breadth of New Zealand, but in this new age of grand enlightenment, for purposes of political-expediency, these most ancient, long-term inhabitants are not allowed to be remembered.

The more general umbrella terms for the original inhabitants were Patu-paiarehe and Turehu, although Maori tribes had many other regional names for the original inhabitants hiding out in the high country after being forced to abandon their former lands of possession to Maori conquerors.

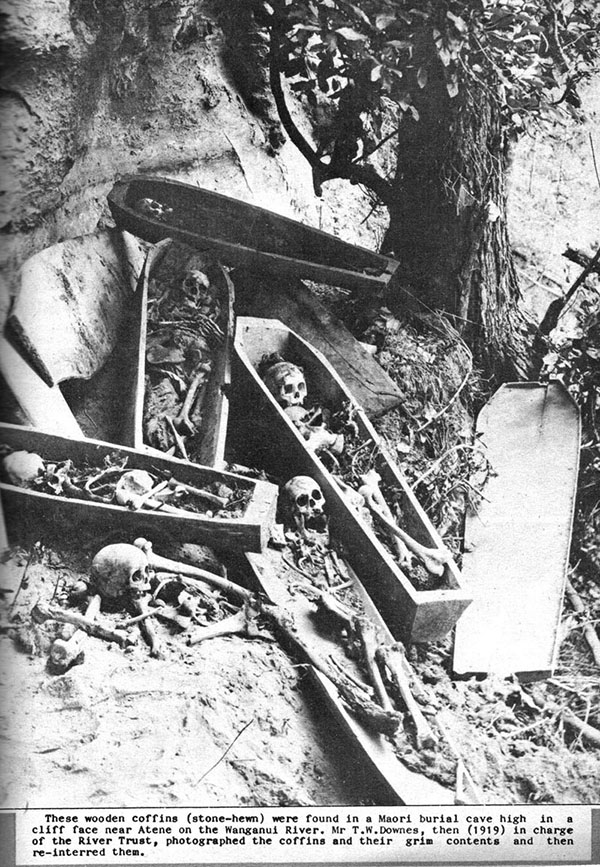

The coffins seen above were photographed in 1919 high up a cliff-face in a very remote and isolated part of New Zealand. Each coffin was hewn by stone tools from a single log, like a dugout canoe.

These coffins were not “planked” or made from sawn timbers, as one would expect colonial European coffins to be fabricated at any point during the colonial era. The coffin lids, seen above, were also hewn from a single, thick plank, with the edge "lip" (used for locking the lid firmly onto the coffin box) carved by scalloping out the central region. The cultural habit of carving coffins in this manner, as single hewn pieces, is reminiscent of the "mummy boards" of Egypt, which encased the body of the deceased.

One skeleton lies on what appears to have been the base of an old canoe.

These skeletons are recognisable European physiology. They were already very old when found in rugged country, far from any European churchyard. The deceased people were obviously the white Ngati Hotu, known in local Maori and European folklore to have hidden from the cannibals for centuries in this inhospitable central North Island region.

The location of this isolated burial cave or shelter was less than 50-miles further into the rugged badlands interior from where the last of the Ngati Hotu tribe were defeated and cannibalised in the "Battle of the Five Forts" at Pukekaikiore (hill of the meal of rats).

A blow-up of the picture positively shows a side view of a jaw (mandible) which is not Maori, but European, lying adjacent to the canoe base. The Polynesian Maori predominantly had a “rocker jaw” with a continuous downwards curve on the lower border. Further to that, the eye sockets of these people are squarish, the nose openings pyramidal, the faces appear long and narrow (dolicephalic skull type) and the craniums very round. The face line from the jaw past the nose and brow is consistent with the European facial profile, rather than the very flat face of the Maori.

Colonial settlers in the vicinity of Artene maintained that there were still Patu-paiarehe people living up in the rugged, forested hills until about 3-4 generations ago.